Next Gen Pau Esparza-Moltó Seeing mitochondria as more than just a powerhouse

Pau Esparza-Moltó was born in a small town near Valencia along Spain’s Mediterranean coast. Now a postdoctoral researcher in Professor Gerald Shadel’s lab, he finds familiarity in his new home of San Diego. “The weather is actually quite similar,” he says. “Very sunny, and when it rains, it pours.”

Growing up in a rural town, Esparza-Moltó fondly recalls an active childhood spent mostly outside—hiking with his parents and brother, picking oranges and persimmons on his grandparents’ land, and playing soccer with friends.

His mother was the first in his family to attend university, and she later became a professor of genetics. Esparza-Moltó shared his mother’s scientific curiosity, but at the time, his attention was also drawn elsewhere—toward music.

In high school, Esparza-Moltó was torn between studying biology and playing the saxophone. “I was always interested in how things work and how things are made,” he says, “especially in the biological sense—like how tiny molecular building blocks can make up entire living organisms.”

Despite this dueling interest between genetics and jazz, Esparza-Moltó ultimately decided to study science in college. At the start of his undergraduate years in Valencia, he considered pursuing medical school but quickly realized anatomy wasn’t for him. Then, he leaned into his lifelong curiosity for “building blocks” and pursued biochemistry and molecular biology to learn more about how genes self-regulate.

Esparza-Moltó did not entirely leave music behind, though. Instead, he used his continued training as a saxophonist to fuel his growth as a scientist.

“Music was how I learned discipline,” says Esparza-Moltó. “Science is a lot of studying, practicing, and repeating experiments over and over. Then after all the discipline and practice, there’s this bit of rest and reflection where you have a piece of music or a piece of data and think, how do I interpret this? What story is it trying to tell?”

Esparza-Moltó finished his bachelor’s degree still gripped by questions about genetics and cellular regulation. His intrigue brought him to Madrid, where he earned a master’s degree at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. But during his time there, Esparza-Moltó surprised himself by pivoting away from fundamental genetics.

“I decided to switch gears for my PhD after hearing some really interesting things about another lab at la Autónoma,” recalls Esparza-Moltó. “They were working on mitochondria, studying the evolution of their function and communication.”

Mitochondria are the small, bean-shaped organelles that generate energy to fuel our cells. Esparza-Moltó hopped on the mitochondria project, excited to dive deeper into the so-called “powerhouse of the cell.” But what intrigued him about the lab’s vision was looking beyond this clichéd identity. “Sure, that’s their most known function,” he says, “but could they also be used in another way?”

To investigate whether mitochondria serve a purpose beyond energy generation, Esparza-Moltó started exploring a protein called ATPase inhibitory factor 1. Instead of supporting mitochondria’s role in energy production, this protein’s activity seemed to be inhibiting it. If mitochondria weren’t going to keep churning out energy, perhaps this protein was helping them carry out another function instead? As he further characterized ATPase inhibitory factor 1, Esparza-Moltó began unveiling a bigger story about how mitochondria relay stress signals to the rest of the cell.

“Our hypothesis is that mitochondrial dysfunction or damage during aging promotes a type of inflammation that then drives the development of liver cancer.”

–Pau Esparza-Moltó

At Salk, Professor Gerald Shadel was reading into the very same story.

“In Spain, it’s very common to go abroad for several months during your PhD to study in another lab,” explains Esparza-Moltó. “After meeting Gerry at a conference in Italy in 2016 and realizing he was good friends with my previous advisor, I thought his lab would be a good fit.”

Esparza-Moltó became a visiting PhD student in Shadel’s lab at Salk, where they established a relationship that brought Esparza-Moltó back years later as a postdoctoral researcher. When he returned to San Diego, Esparza-Moltó eagerly continued his research on mitochondria, but now in a new context—aging.

“The risk of developing different neurological disorders gets higher with age,” says Esparza-Moltó. “We really want to know what the mitochondria are doing in these pathological contexts, like how oxidative stress and inflammation may relate to Alzheimer’s disease.”

Oxidative stress is an imbalance of reactive oxygen molecules brought on by lifestyle and environmental exposures. Mitochondria are the main site of this dysfunction, and the main victims of its damaging effects. Shadel’s lab has discovered important links between mitochondria, oxidative stress, and inflammation across the brain and body.

One way that Esparza-Moltó researches mitochondria is with sophisticated cultures of patient-derived skin cells, called fibroblasts. Salk scientists can turn these cells into what are called “induced neurons,” allowing them to easily access and study human neurons in the lab. While developing and studying these cells with the help of Salk Professor Rusty Gage, Esparza-Moltó made an interesting discovery. He found a specific group of proteins were relocating to mitochondria when the cells were under stress. “We need to follow up on the relevance of these proteins and what they’re doing there,” adds Esparza-Moltó.

Esparza-Moltó is also collaborating with cancer biologists and immunologists at Salk to understand the role of mitochondria in other disease contexts.

“The incidence of cancer also increases as we age—especially so in the case of liver cancer,” says Esparza-Moltó. “Our hypothesis is that mitochondrial dysfunction or damage during aging promotes a type of inflammation that drives the development of liver cancer.”

The multitude of collaborations and engagements he’s involved in—including Salk’s American Heart Association-Allen Initiative in Brain Health and Cognitive Impairment—have kept Esparza-Moltó quite busy since settling in California, but he is beginning to explore new interests outside of science.

“I started surfing, but I don’t think it’s really my thing,” laughs Esparza-Moltó. “But I did recently get a dog that I walk and explore the city with.. And there are so many opportunities to hike all around San Diego—I really like doing that.”

Though he’s a country’s width and a cross-Atlantic flight away from Spain, family remains important to Esparza-Moltó, who makes time to travel back for visits at least once a year. He also keeps his artistic sensibilities alive through new creative hobbies, like cooking.

“I am always looking for the best technique or approach to get me to my goal, whether that’s a new recipe, song, or research question,” says Esparza-Moltó. “To this day, when innovating or changing directions, I definitely let my musical and creative principles guide me.”

Featured Stories

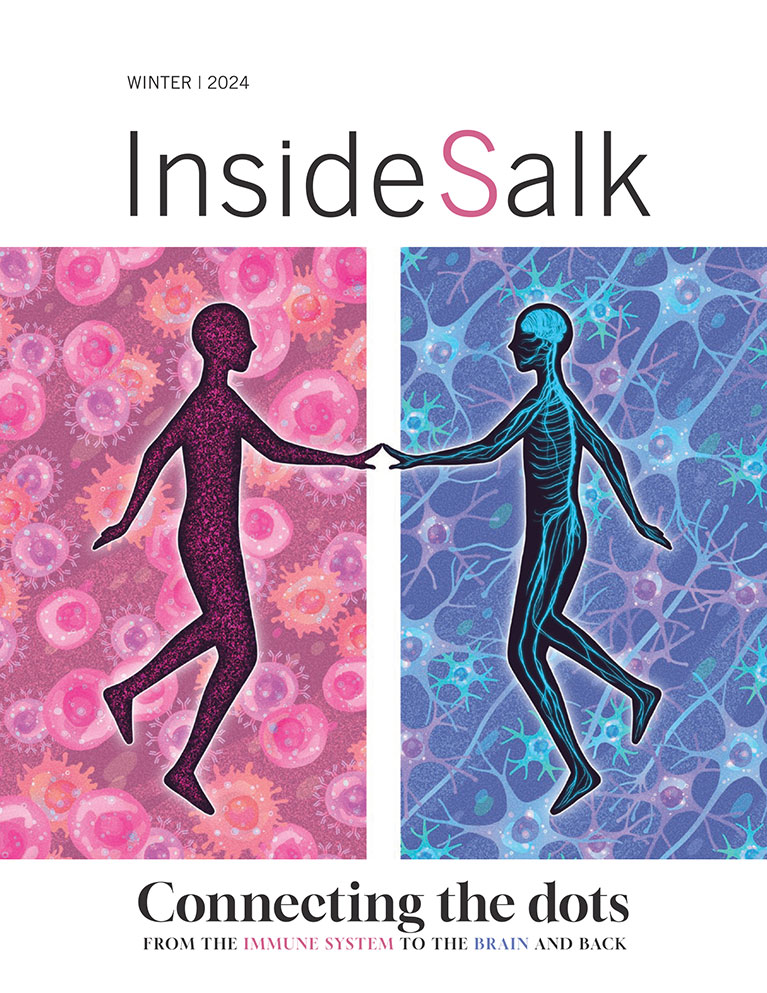

Connecting the dots—From the immune system to the brain and back againBy collaborating across disciplines like genetics, neuroscience, and immunology, Salk scientists are uniquely positioned to lead us into a future of healthier aging and effective therapeutics for Alzheimer’s.

Connecting the dots—From the immune system to the brain and back againBy collaborating across disciplines like genetics, neuroscience, and immunology, Salk scientists are uniquely positioned to lead us into a future of healthier aging and effective therapeutics for Alzheimer’s. Salk mourns the loss of Joanne ChorySalk Professor Joanne Chory, one of the world’s preeminent plant biologists who led the charge to mitigate climate change with plant-based solutions, died on November 12, 2024, at the age of 69 due to complications from Parkinson’s disease.

Salk mourns the loss of Joanne ChorySalk Professor Joanne Chory, one of the world’s preeminent plant biologists who led the charge to mitigate climate change with plant-based solutions, died on November 12, 2024, at the age of 69 due to complications from Parkinson’s disease.  Talmo Pereira—From video game bots to leading-edge AI toolsTalmo Pereira is a Salk Fellow, a unique role that empowers scientists to move straight from graduate school to leading their own research groups without postdoctoral training.

Talmo Pereira—From video game bots to leading-edge AI toolsTalmo Pereira is a Salk Fellow, a unique role that empowers scientists to move straight from graduate school to leading their own research groups without postdoctoral training. Kay Watt—From Peace Corps to plant scienceAt the heart of the Harnessing Plants Initiative is Program Manager Kay Watt who tackles all of the strategy, site operations, budgeting, reporting, communication, and outreach that keep the whole program on track.

Kay Watt—From Peace Corps to plant scienceAt the heart of the Harnessing Plants Initiative is Program Manager Kay Watt who tackles all of the strategy, site operations, budgeting, reporting, communication, and outreach that keep the whole program on track.  Pau Esparza-Moltó—Seeing mitochondria as more than just a powerhousePau Esparza-Moltó, a postdoctoral researcher in Professor Gerald Shadel’s lab, finds comfort in the similarities between his hometown in Spain and San Diego, where he now studies cell-powering mitochondria.

Pau Esparza-Moltó—Seeing mitochondria as more than just a powerhousePau Esparza-Moltó, a postdoctoral researcher in Professor Gerald Shadel’s lab, finds comfort in the similarities between his hometown in Spain and San Diego, where he now studies cell-powering mitochondria. Salk summer programs bring equity and opportunity to the STEM career pipelineThe Salk Institute recently hosted two inaugural events designed to enhance diversity within the scientific community: the Rising Stars Symposium and the Diverse Inclusive Scientific Community Offering a Vision for an Ecosystem Reimagined (DISCOVER) Symposium.

Salk summer programs bring equity and opportunity to the STEM career pipelineThe Salk Institute recently hosted two inaugural events designed to enhance diversity within the scientific community: the Rising Stars Symposium and the Diverse Inclusive Scientific Community Offering a Vision for an Ecosystem Reimagined (DISCOVER) Symposium.