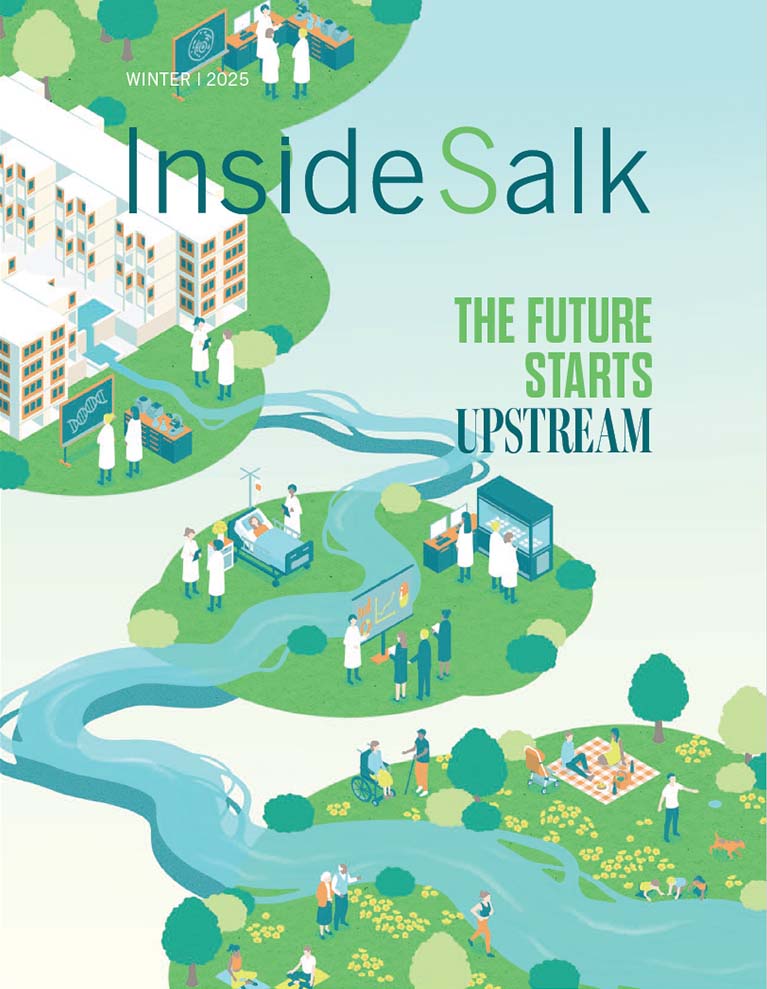

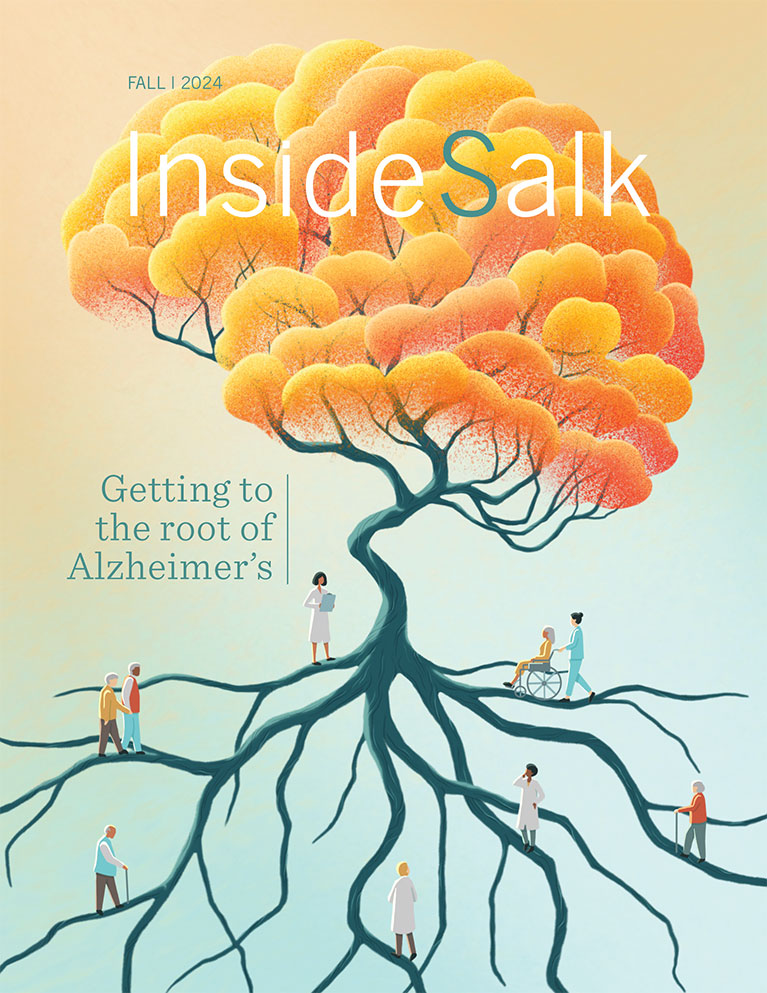

The future starts upstream Foundational discoveries are the source of tomorrow’s breakthroughs, but what happens if we let the river run dry?

WHEN JONAS SALK DEBUTED THE FIRST EFFECTIVE POLIO VACCINE IN 1955, MANY ASSUMED HIS NEXT ENDEAVOR—THE SALK INSTITUTE—WOULD FOCUS ON VACCINE DEVELOPMENT. Instead, he designed the coastal campus to be a gathering place where the world’s top scientists could study the fundamental mysteries of life. He knew the biggest scientific breakthroughs happen when researchers have the opportunity to work together and ask foundational questions.

“We don’t do science to make money. We do it to make discoveries, which we give back to society.” –Gerald Joyce

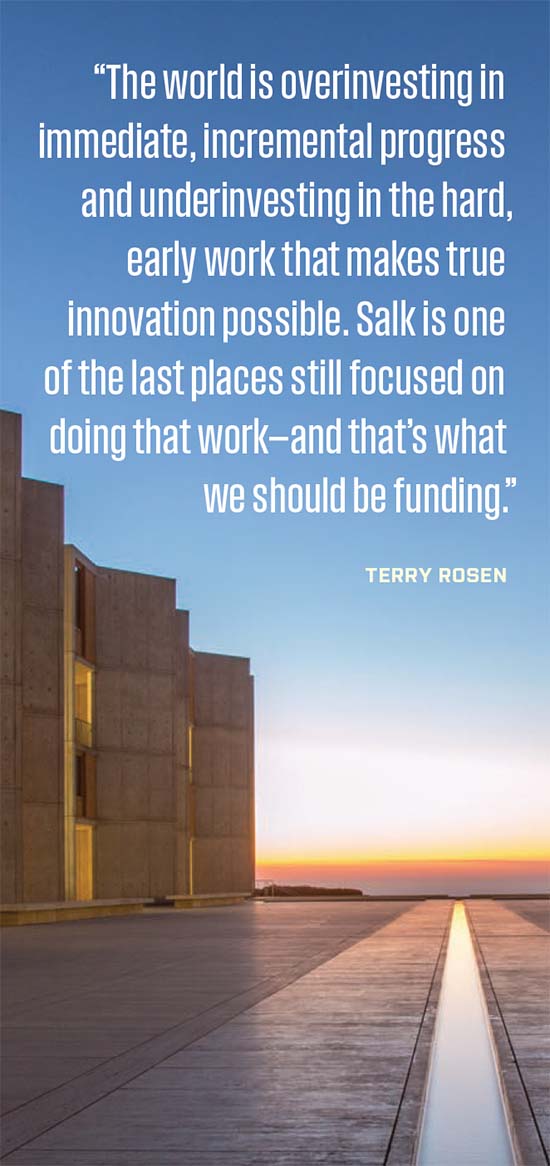

This mission was embodied by one of the Institute’s landmark architectural features, which he dubbed the River of Life—a stream that flows through the central Courtyard toward the horizon, where it appears to merge with the distant sea. It symbolizes the constant stream of discoveries flowing out of the Institute’s labs and into humanity’s greater body of knowledge.

Today, the River of Life is more than an inspiring symbol of Salk science; It’s a powerful reminder of why foundational research deserves our support.

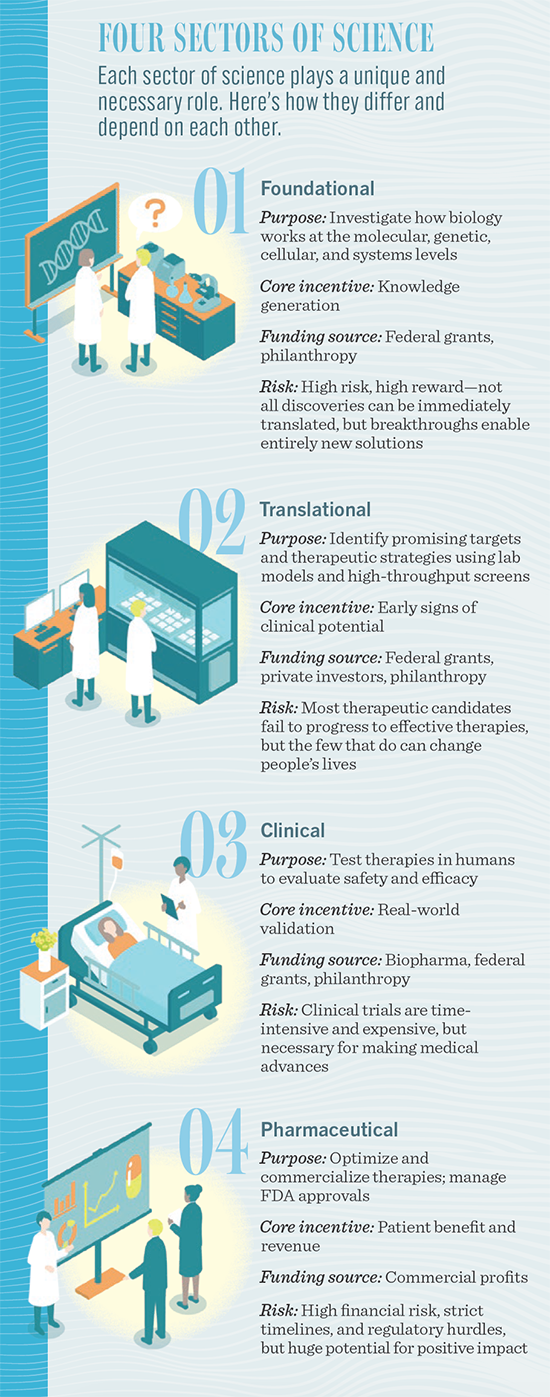

Salk is now one of the few institutions that remain fully dedicated to “basic science”—research that asks fundamental questions and generates foundational knowledge. In a healthy science ecosystem, this knowledge naturally flows into translational, clinical, and pharmaceutical sectors, enabling new technologies and treatments that improve our quality of life. Innovations like cancer immunotherapy, CRISPR gene editing, and GLP-1 weight loss drugs are now household names, but they all got their start as basic discoveries in a lab.

The issue is that science funding has increasingly prioritized the later stages of research and commercialization, leaving foundational science more vulnerable than ever.

“We don’t do science to make money,” says Salk President Gerald Joyce, MD, PhD. “We do it to make discoveries, which we give back to society. The insights we generate are what ultimately fuel the biotech and pharmaceutical industries. We need to replenish this river of knowledge or the whole ecosystem will run dry.”

THE COST OF SHORT-TERM THINKING

AT A GLANCE, MODERN SCIENCE SEEMS TO BE THRIVING. Pharmaceutical companies race to develop new drugs. AI-powered diagnostics promise earlier detection of disease. Biotech startups draw billions in investor funding. But underneath all that momentum lies a quieter crisis: The foundational science that enables all this innovation is losing critical support, with funders prioritizing projects that promise more immediate returns.

Terry Rosen, PhD, a biotech entrepreneur and vice chair of Salk’s Board of Trustees, has seen firsthand how foundational science fuels the biomedical economy. As co-founder and CEO of Arcus Biosciences, he’s grown concerned about recent shifts in the scientific ecosystem.

“All the best medicines we have right now are the result of earlier foundational discoveries that laid the groundwork for new clinical strategies. The Salk Institute has always been a key contributor to this body of foundational research,” Rosen says. “Translation of those discoveries has been the bedrock of modern medicine and recent therapeutic advances, but most of the low-hanging fruit has now been picked. If society stops investing in foundational science, the innovation pipeline will eventually collapse.”

Rosen says new structural and financial stressors have pushed academia and industry away from deeper fundamental inquiry toward short-term, applied projects. With companies being pressured to show quarterly profits and universities competing for a shrinking pool of grants, both are encouraged to focus their resources on the fastest and most easily translatable science.

“The science that gives rise to real innovation and cures often takes decades of deep, risky, long-term work. And fewer and fewer people are doing it.” –Terry Rosen

The urgency is understandable. Federal funders, investors, and philanthropists all want to be sure that their support will yield tangible results in the near future.

Yet many of today’s top therapies trace their lineage back to discoveries made decades earlier by scientists who had the opportunity and support to ask big, open-ended questions. Rosen says the same opportunities are not being afforded to today’s scientists.

“Everyone’s trying to plant tulips they can see bloom in three months,” Rosen says. “But the science that gives rise to real innovation and cures often takes decades of deep, risky, long-term work. And fewer and fewer people are doing it.”

President Joyce also speaks from experience, having previously directed the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation (GNF).

“What pharmaceutical companies do is very important, but that applied research is very different from the foundational research being done at a place like Salk,” says Joyce. “A company’s experiments are designed to provide more immediate results, and projects that aren’t progressing fast enough will be shut down. This is a reasonable stance for a commercial organization that cannot undertake risky, early-stage projects that may only yield returns after a decade or more. These long-term opportunities are what nonprofit science is for.”

Rosen says pharmaceutical companies are also increasingly relying on smaller biotech companies and startups to do much of the initial research and development. These groups take on the risky business of early-stage drug discovery and development, with larger corporations often acquiring them once a promising product is in sight.

These days, though, even nonindustry scientists are shifting toward safer, short-term bets. In the past, an academic researcher trying to understand which genes and molecules drive a biological process might not have known what the future impact of their findings would be. Today, the same scientist is expected to outline the clinical applications of their experiments before they can get the money to do them. With federal funding cuts making the grant process even more competitive, researchers have no choice but to tailor their experiments to funders’ preferences.

“Academic scientists are being pushed to act like drug companies, but with a tiny fraction of the resources,” says Rosen. “How many institutions have set up high-throughput screening and drug discovery programs to attract translational funding? We shouldn’t expect academics to do the same work as industry scientists. The faculty at Salk are extremely brilliant and creative scientists, and when they’re given the opportunity and freedom to do what they do best, we all benefit.”

TODAY’S QUESTIONS, TOMORROW’S SOLUTIONS

SINCE ITS FOUNDING, SALK HAS MAINTAINED A SPECIAL PLACE IN THE SCIENCE ECOSYSTEM. As an independent, nonprofit, basic research institute, it is uniquely designed to support the kind of foundational discoveries the other sectors rely on.

The Institute’s scale has been intentionally optimized: small enough to allow close collaborative relationships, but large enough to cover a breadth of research areas. Faculty are unified by big questions, not separated by departments. With fewer academic responsibilities and a dedicated administrative staff to support operational tasks, Salk scientists can focus more of their energy on their research, interacting with colleagues, and generating new ideas.

“The collaborative culture and sheer diversity of science at Salk make a real difference,” says Chief Science Officer Jan Karlseder, PhD. “When people with completely different expertise work on the same problem, that’s when real breakthroughs happen.”

Karlseder says Salk is a leader in “use-inspired basic research”—foundational science that isn’t necessarily pursued for its immediate application but still has clear implications for health and disease. The Institute’s academic governance committees work to identify the most promising research areas and strategically recruit scientists who are at the forefront of those fields.

“We think very hard about what the most important questions in biology are and what teams we can assemble to make the biggest impact,” Karlseder says. “The right people asking the right question is what unlocks entirely new fields.”

Take Salk molecular biologist Tony Hunter, PhD. When he joined the Institute’s faculty in 1975, he set out to learn how viruses turn healthy cells into cancer cells. This research led to his discovery of tyrosine phosphorylation, a molecular switch that controls cell growth and division. Hunter’s later work also explained how the enzymes that drive this switch, called tyrosine kinases, become overactive in cancer and lead to tumor growth.

At the time, these were basic insights into cellular biology. But with the help of translational, clinical, and pharmaceutical partners, they led to the approval of over 80 different cancer-fighting drugs, including the 2001 debut of Novartis’ Gleevec, a groundbreaking medicine that targets tyrosine kinases.

Hunter’s research didn’t start as a drug discovery project. He was asking a fundamental question about how biology works. But the answer completely changed the way we treat cancer and saved millions of lives.

“We want the public to understand that foundational science isn’t separate from translation—it’s married to it,” says Karlseder. “Every advance in translational science begins with someone asking a fundamental question. We’re still the place that asks those questions first.”

Salk scientists are now answering questions that are changing the way we think about cancer, aging, Alzheimer’s, allergies, agriculture, and more.

When there’s a clear opportunity to translate these discoveries, the Institute doesn’t shy away from kick-starting that process. But its core mission is to push the boundaries of what is known and use those insights to move science and society forward.

“Salk has always been what science needs most at each moment in history,” says Karlseder. “Biology used to be about taking things apart and figuring out what they’re made of. Now it’s about putting them back together and understanding how they make us who we are. The great questions ahead are integrative, and that’s exactly what Salk was built to do.”

KEEP THE RIVER FLOWING

SCIENCE HAS ALWAYS DEPENDED ON THE PARTNERSHIP BETWEEN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE FUNDING. But philanthropy has been especially crucial in enabling the most high-risk, high-reward projects.

For example, Salk’s Innovation and Collaboration Grants were launched with support from Joan and Irwin Jacobs. This internal funding source supports creative early-stage ideas that would be considered too risky or novel for traditional federal grant applications.

Philanthropy also helps the Institute train the next generation of foundational scientists. With universities increasingly preparing graduate students to get jobs in industry, fewer trainees are being encouraged to pursue basic science. At Salk, summer training programs supported by the Prebys Foundation and postdoctoral research fellowships funded by the Brown Foundation and La Mer are among the many ways that private funding helps replenish the pool of foundational scientists.

Now, as the cost of modern research continues to rise, Rosen says donors will need to step in where federal funders have retreated.

“There are still many complex health issues that we all need solutions for, and everyone wants to see us get there as quickly as possible,” he says. “But throwing more money at the same science won’t lead to better outcomes. The world is overinvesting in immediate, incremental progress and underinvesting in the hard, early work that makes true innovation possible. Salk is one of the last places still focused on doing that work—and that’s what we should be funding.”

What Rosen and other Salk supporters understand is that basic science is not a luxury; it’s the foundation on which every cure, innovation, and industry depends.

Behind every history-changing achievement from scientists like Jonas Salk was the visionary support of their public and private funders. Donors and taxpayers have both played an essential role in this progress, strengthening the current of the river of life. At the end of the day, breakthroughs don’t really begin up the river or in the lab; they begin with you.

Featured Stories

The future starts upstreamFoundational discoveries are the source of tomorrow’s breakthroughs, but what happens if we let the river run dry?

The future starts upstreamFoundational discoveries are the source of tomorrow’s breakthroughs, but what happens if we let the river run dry? Diana Hargreaves: Follow the ScienceThe BAF complex is near and dear to Diana Hargreaves, PhD, a scientist, professor, and the J.W. Kieckhefer Foundation Chair at Salk. Hargreaves was born in Atlanta, Georgia, to a physician-scientist mother, so science had a hold on her from the very beginning.

Diana Hargreaves: Follow the ScienceThe BAF complex is near and dear to Diana Hargreaves, PhD, a scientist, professor, and the J.W. Kieckhefer Foundation Chair at Salk. Hargreaves was born in Atlanta, Georgia, to a physician-scientist mother, so science had a hold on her from the very beginning. Ana Cabrera: Clearing the Path to DiscoveryCabrera is the senior director of strategic operations at Salk, a right-hand role to Chief Science Officer (CSO) Jan Karlseder, PhD. Cabrera and her colleagues in the CSO’s Office support Salk scientists through all of the logistical challenges that stand between them and their potential.

Ana Cabrera: Clearing the Path to DiscoveryCabrera is the senior director of strategic operations at Salk, a right-hand role to Chief Science Officer (CSO) Jan Karlseder, PhD. Cabrera and her colleagues in the CSO’s Office support Salk scientists through all of the logistical challenges that stand between them and their potential. Aksinya Derevyanko: Finding strength in science, stage, and synapsesDerevyanko is a postdoctoral researcher training under Nicola Allen, PhD, a professor and neuroscientist at Salk.

Aksinya Derevyanko: Finding strength in science, stage, and synapsesDerevyanko is a postdoctoral researcher training under Nicola Allen, PhD, a professor and neuroscientist at Salk.