Next Gen Lara Labarta-Bajo An immunologist’s journey from Barcelona and ballet to the brain

Whether dancing in Spain or surfing in San Diego, Lara Labarta-Bajo has always celebrated the power of the human body. Now a postdoctoral researcher in Associate Professor Nicola Allen’s lab at Salk, she studies how the immune system connects the body to the brain and how this relationship evolves as we age.

Labarta-Bajo grew up in Barcelona, a seaside city that doubles as a science education and industry hub.

“It’s funny, people compare it to San Diego,” says Labarta-Bajo, “and some will even refer to the region as ‘little California.’”

Outside, she was swaddled by the sun and sea. At home, she was surrounded by numbers. Both her parents are engineers, and her brother a mathematician, “but I was more interested in the biology of our bodies.”

Labarta-Bajo was an active child, always on the move. She spent most of her youth out in nature, playing sports, or dancing ballet. “Ballet really wires your brain in a certain way,” she says. “It makes you move in a very controlled manner, so you become aware of every muscle in your body.”

This deep awareness of her mind and body led Labarta-Bajo to pursue an undergraduate degree in biology. But while each class provided a peek into a different part of the body, she found herself most excited when studying its physiology as a whole. Then, during a summer internship in a lab at Virginia Tech, she found a way to satiate her wide-ranging interests.

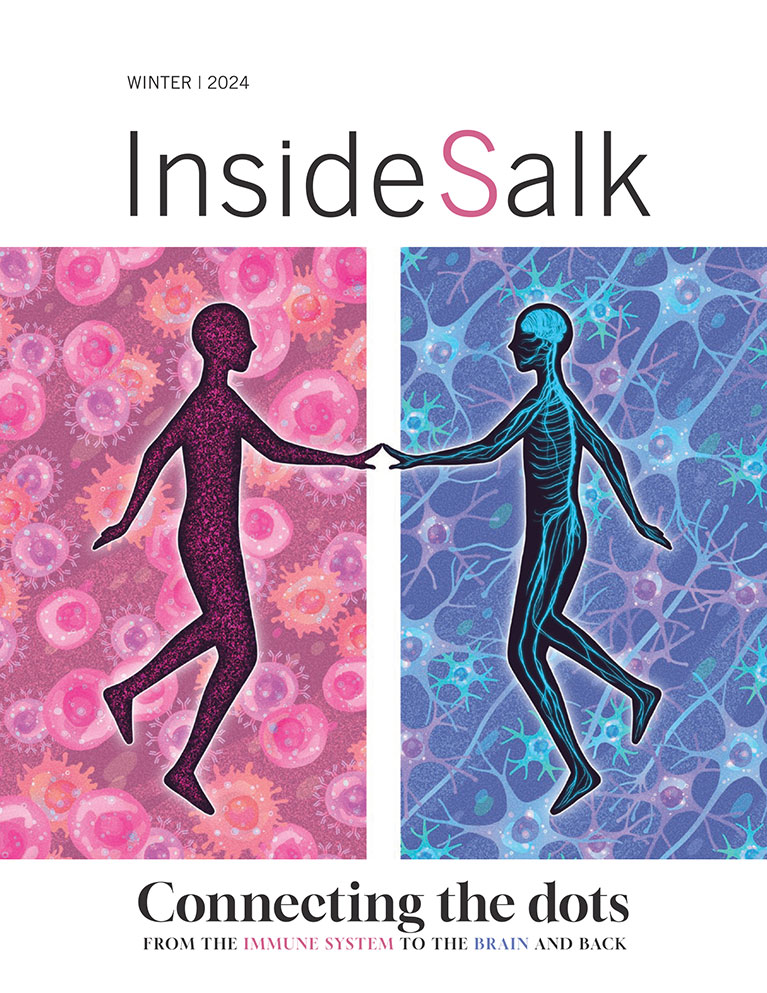

“Immunology is a field that gives you a very systems-level view of your body, meaning it’s not restricted to one location,” says Labarta-Bajo. “Your immune system moves around your body, visiting your skin, your brain, your intestines. It’s constantly circulating, surveying, making sure everything is in place. So I felt like the immune system was a window for me to better understand how our bodies work.”

Labarta-Bajo went on to study the intricacies of the immune system through her graduate research at UC San Diego. During that time, she explored the body’s response to chronic infection and how that constant immune activity can affect our gut health. She’s since returned to her ballet-inspired interests by studying the connection between the brain and body here at Salk.

“When we’re born, we have a nervous system, and we have an immune system,” she says. “As we go through life, the immune system matures and ages, and so does the nervous system. So how is it possible that these two systems are present but don’t talk to each other? That was an intriguing question to me. I don’t think it’s possible—I think they talk to each other often.”

Her instincts appear to be correct, based on a growing body of research on the immune activity in and around the brain. Allen is a trailblazer in this field and an expert on a type of brain immune cell called astrocytes. These star-shaped cells were traditionally thought to simply feed and protect our neurons—the cells whose electrical signals are responsible for all our thoughts, feelings, and actions. But scientists like Allen and Labarta-Bajo are helping us realize that astrocytes may have a much larger role in brain function than was previously appreciated.

The immune system’s primary job is to find and destroy invading pathogens, but it also has to tell the rest of the body that this battle is happening. These messages come in the form of inflammatory signals, which serve as helpful warnings when sent in moderation but can become damaging in excess.

“Astrocytes are at the interface between your neurons and the rest of your body,” says Labarta-Bajo. “They have this privileged position where they can read the memos that are getting sent through the blood in the form of inflammatory molecules. Your astrocytes are picking up the message, deciding how to interpret it, and conveying the message to the neurons. And that’s what we’re working on in the lab—how does this peripheral threat affect your brain?”

Labarta-Bajo and her colleagues are now identifying specific molecules that astrocytes use to read the incoming memos and trigger inflammatory responses in the brain. She’s also especially interested in how this communication between the immune and nervous systems evolves throughout our lives.

Aging is associated with higher levels of inflammation across many organ systems, including the brain. But, interestingly, Allen’s lab is finding that astrocytes become especially inflammatory in brain regions that control how we move.

“When we manipulate the activity of certain molecules in a mouse’s astrocytes, we can see that has an effect on the way the mouse moves,” says Labarta-Bajo. “So maybe we can manipulate these molecules during aging to delay the loss of motor abilities. That’s the question now—how can we manipulate astrocytes to improve our brain function?”

Labarta-Bajo is hopeful this work will lead to future therapeutics for reducing brain inflammation and maintaining mobility in later life. In the meantime, she’s looking forward to many more years of science and surfing ahead of her.

“It really gets me excited to see the new frontiers we can push,” she says, “by having astrocytes and the immune system at the center of it all.”

Lara Labarta-Bajo | Beyond Lab Walls Podcast

How can an infection in your lungs have such a lasting effect on your brain? Her latest findings reveal a surprising relationship between infections, brain aging, and mobility.

Featured Stories

Getting to the root of Alzheimer’sSalk scientists are teaming up to understand brain aging. By collaborating across disciplines like genetics, neuroscience, and immunology, our researchers are uniquely positioned to lead us into a future of healthier aging and effective therapeutics for Alzheimer’s.

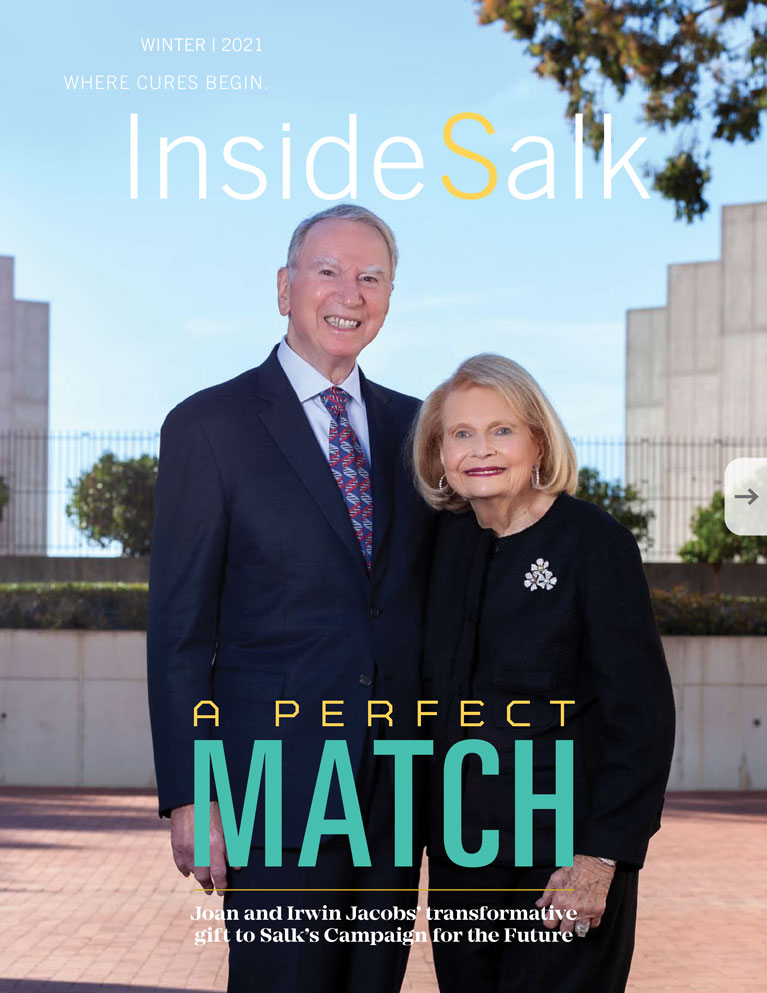

Getting to the root of Alzheimer’sSalk scientists are teaming up to understand brain aging. By collaborating across disciplines like genetics, neuroscience, and immunology, our researchers are uniquely positioned to lead us into a future of healthier aging and effective therapeutics for Alzheimer’s. Salk mourns the loss of Joan JacobsThe Salk Institute lost one of its greatest supporters and one of San Diego’s most generous philanthropists when Joan Jacobs died on May 6, 2024, in La Jolla, California. She was 91 years old.

Salk mourns the loss of Joan JacobsThe Salk Institute lost one of its greatest supporters and one of San Diego’s most generous philanthropists when Joan Jacobs died on May 6, 2024, in La Jolla, California. She was 91 years old. Axel Nimmerjahn— Widening perspectives through plane windows and microscope lensesInside Salk sat down with Nimmerjahn to hear how he went from curious child to world renowned researcher. Now a professor at Salk, he studies the central nervous system and designs new tools—like mini microscopes!—to study the system's various cell types.

Axel Nimmerjahn— Widening perspectives through plane windows and microscope lensesInside Salk sat down with Nimmerjahn to hear how he went from curious child to world renowned researcher. Now a professor at Salk, he studies the central nervous system and designs new tools—like mini microscopes!—to study the system's various cell types. Jálin Johnson— Enhancing equity and inclusion at Salk and beyondOver the course of nearly 30 years dedicated to advocacy work, Jálin B. Johnson has served those in need and has given a voice to the voiceless—a principle that has guided her throughout her career. This commitment continues to shape her work as she steps into the role of director of Salk’s Office of Equity & Inclusion.

Jálin Johnson— Enhancing equity and inclusion at Salk and beyondOver the course of nearly 30 years dedicated to advocacy work, Jálin B. Johnson has served those in need and has given a voice to the voiceless—a principle that has guided her throughout her career. This commitment continues to shape her work as she steps into the role of director of Salk’s Office of Equity & Inclusion. Lara Labarta-Bajo—An immunologist’s journey from Barcelona and ballet to the brainWhether dancing in Spain or surfing in San Diego, Lara Labarta-Bajo has always celebrated the power of the human body. Now a postdoctoral researcher in Associate Professor Nicola Allen’s lab at Salk, she studies how the immune system connects the body to the brain and how this relationship evolves as we age.

Lara Labarta-Bajo—An immunologist’s journey from Barcelona and ballet to the brainWhether dancing in Spain or surfing in San Diego, Lara Labarta-Bajo has always celebrated the power of the human body. Now a postdoctoral researcher in Associate Professor Nicola Allen’s lab at Salk, she studies how the immune system connects the body to the brain and how this relationship evolves as we age. Professor or partner? Luc Jansen’s switch from science to lawDashed dreams of medical school brought Jansen to Salk's campus back in 2003, where he simultaneously contemplated a career in scientific research and a career in big law. Though he decided on law in the end, Jansen's affection for Salk remains as he now hosts Salk gatherings in his New York City office and excitedly shares the enduring importance of basic science.

Professor or partner? Luc Jansen’s switch from science to lawDashed dreams of medical school brought Jansen to Salk's campus back in 2003, where he simultaneously contemplated a career in scientific research and a career in big law. Though he decided on law in the end, Jansen's affection for Salk remains as he now hosts Salk gatherings in his New York City office and excitedly shares the enduring importance of basic science. Rising Stars and DISCOVER programs provide new opportunities for trainees from underserved backgroundsThe Salk Institute recently hosted two inaugural events designed to enhance diversity within the scientific community: the Rising Stars Symposium and the Diverse Inclusive Scientific Community Offering a Vision for an Ecosystem Reimagined (DISCOVER) Symposium.

Rising Stars and DISCOVER programs provide new opportunities for trainees from underserved backgroundsThe Salk Institute recently hosted two inaugural events designed to enhance diversity within the scientific community: the Rising Stars Symposium and the Diverse Inclusive Scientific Community Offering a Vision for an Ecosystem Reimagined (DISCOVER) Symposium.