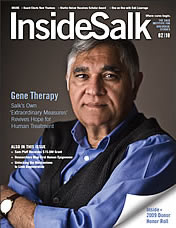

Special Feature 50 years of discovery Professor Tony Hunter’s half-century legacy at Salk

Tony Hunter first arrived at the Salk Institute in 1971 as a postdoctoral trainee from the University of Cambridge. He immediately embraced the Institute’s collaborative culture and the Southern California lifestyle (and hairstyle!), forming lifelong connections with colleagues. Long hours in the lab were balanced with adventurous outings like desert camping and river rafting—hobbies he continues to this day.

After two years at Salk, Hunter returned to Cambridge but soon found his prospects there lacking. Following a challenging year of living with friends and his lab burning down, he decided to rejoin Salk as an assistant professor in 1975.

“When I came back to Salk, I didn’t have long-term plans or a clear vision for my career,” Hunter says. “I never imagined I’d still be here 50 years later, but I’m happy with how things worked out. The collaborative and innovative spirit of the Institute keeps me inspired.”

On February 21, Salk celebrated Hunter’s 50 years as a cancer biology pioneer with a symposium titled “50 Years of Rafting the River of Life.” The event featured lab alumni, colleagues, and other cancer research luminaries sharing their science, memories, and tributes.

“Tony Hunter is a towering figure in science,” says Salk President Gerald Joyce. “His discoveries have transformed cancer biology and led to therapies that have saved countless lives. His dedication, collaborative spirit, and brilliance have left an indelible mark.”

“I never imagined I’d still be here [at the Salk Institute] 50 years later, but I’m happy with how things worked out. The collaborative and innovative spirit of the Institute keeps me inspired.”

–Professor Tony Hunter

In 1979, while studying tumor viruses in his Salk lab, Hunter serendipitously discovered a molecular switch that controls cell growth and division, known as tyrosine phosphorylation. It quickly became a landmark study in cancer biology.

Hunter’s research later revealed how certain tyrosine kinases, the enzymes that drive this switch, become overactive in cancers, spurring uncontrolled cell proliferation.

Hunter’s discovery inspired the development of more than 80 FDA-approved cancer drugs that target protein kinases. One of the most notable drugs in this class is imatinib, commonly known as Gleevec, which has transformed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) from a fatal disease into a manageable chronic condition.

Over the decades, Hunter’s research has spanned a remarkable breadth of scientific areas, from pancreatic cancer to DNA tumor viruses to protein phosphorylation and beyond. One recent Salk study builds on several decades of research in the Hunter lab. In 1996, Hunter’s team discovered a protein called PIN1. Now, the team has uncovered how it drives bladder cancer development by increasing cholesterol production. Hunter’s team is now exploring drug combinations that can target PIN1 and reduce cholesterol to block bladder tumor growth (see cancer discoveries).

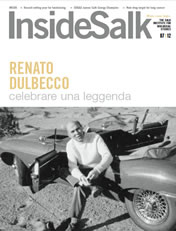

Tony Hunter stands in front of a small sampling of his enormous collection of science and symposia T-shirts, displayed during his 50th anniversary symposium.

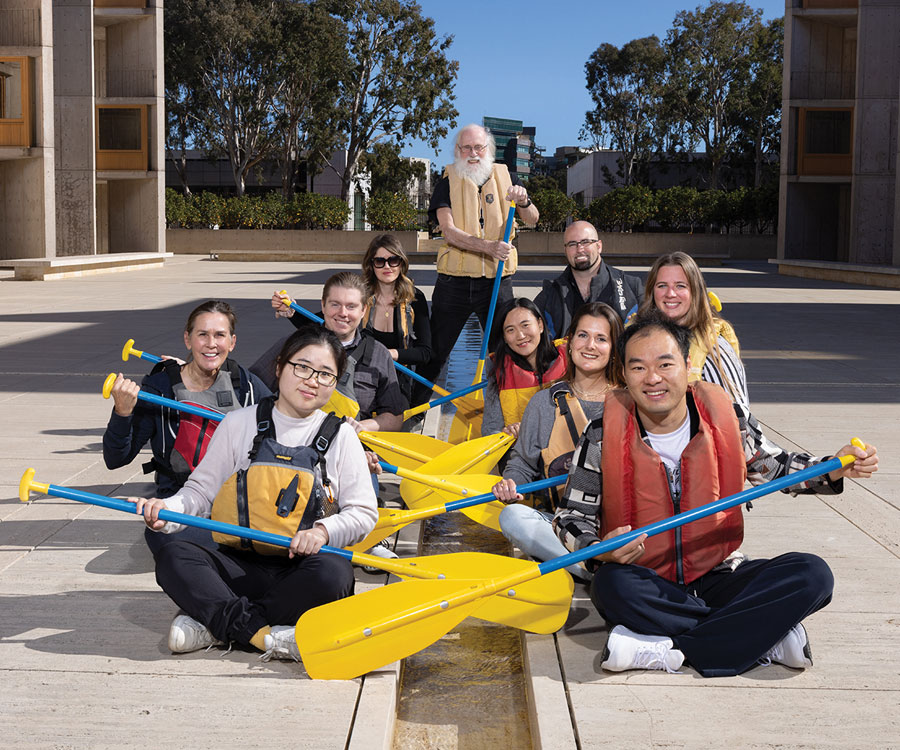

Members of Hunter’s lab pay tribute to his favorite hobby by “rafting” in the Salk Courtyard’s River of Life water feature.

Beyond his scientific achievements, Hunter has mentored more than 100 trainees, many of whom have become scientific leaders. “I’m proud of the science we’ve accomplished, but also of the people I’ve trained and collaborated with,” he says.

Known for his long beard, witty science-themed T-shirts, and extensive collection of handwritten notebooks, Hunter has helped define Salk’s culture.

“Tony is not just a brilliant scientist but an incredibly generous and collaborative colleague,” says Salk Professor Ronald Evans. “When I first arrived at Salk, Tony was the first person I met. He even lent me his car until I could get my own. He revolutionized cancer treatments, but what sets Tony apart is his willingness to share insights and tools, elevating the work of everyone around him.”

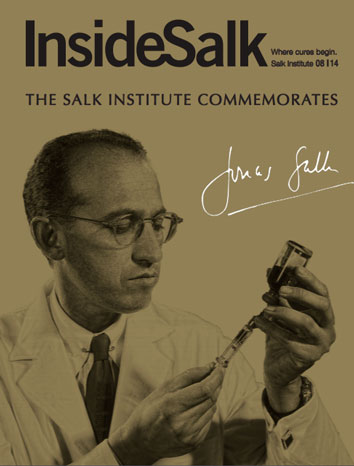

Reflecting on Hunter’s career, longtime colleague Salk Professor Emeritus Geoffrey Wahl is reminded of a famous quote by Jonas Salk—“Our greatest responsibility is to be good ancestors”—although Wahl recalls Salk saying “wise ancestors.”

“Either way, Tony has always been both good and wise,” Wahl says. “Despite his fame, he’s humble and accessible. You can always ask him a question, and if he doesn’t know the answer, he’ll help you find it.”

This is Hunter’s advice to young scientists: “Find something you’re passionate about. Choose a problem where your success will make an impact. Science is a long journey, but if you follow your curiosity, you’ll never be bored.”

Featured Stories

Seeds of change: The Harnessing Plants Initiative is scaling a new kind of crop that could save the future of farming—and the planetFarmers and plant biologists are linking arms to build more sustainable, resilient agriculture. Salk scientists are working to enhance plants' natural ability to capture carbon to clean our air and restore environmental stability—all while maintaining productivity for growers.

Seeds of change: The Harnessing Plants Initiative is scaling a new kind of crop that could save the future of farming—and the planetFarmers and plant biologists are linking arms to build more sustainable, resilient agriculture. Salk scientists are working to enhance plants' natural ability to capture carbon to clean our air and restore environmental stability—all while maintaining productivity for growers. The day polio met its match: Celebrating 70 years of the Salk vaccineSeventy years ago, on April 12, 1955, the polio vaccine developed by Jonas Salk and his colleagues was officially declared “safe, effective, and potent”—a moment heralded as a triumph of medicine over one of the most feared diseases of the 20th century. On this milestone anniversary, it's crucial to remember that fear, and learn from this historic public health success.

The day polio met its match: Celebrating 70 years of the Salk vaccineSeventy years ago, on April 12, 1955, the polio vaccine developed by Jonas Salk and his colleagues was officially declared “safe, effective, and potent”—a moment heralded as a triumph of medicine over one of the most feared diseases of the 20th century. On this milestone anniversary, it's crucial to remember that fear, and learn from this historic public health success. Pallav Kosuri: Making magic out of moleculesA physicist-turned-bioengineer, Kosuri is developing nanoscale technologies that are on their way to transforming how we diagnose and treat diseases. Kosuri’s lab is using DNA to create a suite of biosensors, diagnostic tools, and drug delivery systems.

Pallav Kosuri: Making magic out of moleculesA physicist-turned-bioengineer, Kosuri is developing nanoscale technologies that are on their way to transforming how we diagnose and treat diseases. Kosuri’s lab is using DNA to create a suite of biosensors, diagnostic tools, and drug delivery systems. Suzanne Page: Uprooting, replanting, and blooming againIn October 2024, the Salk Institute named Suzanne Page as its new Vice President and Chief Operating Officer. Page has lived and traveled all over the country, developing a strong background in research operations, finance, and legal in the for-profit and nonprofit sectors—leading her to "manifest" her role at Salk.

Suzanne Page: Uprooting, replanting, and blooming againIn October 2024, the Salk Institute named Suzanne Page as its new Vice President and Chief Operating Officer. Page has lived and traveled all over the country, developing a strong background in research operations, finance, and legal in the for-profit and nonprofit sectors—leading her to "manifest" her role at Salk. Irene López Gutiérrez: After every storm comes sunshine—and scienceRainy winter weather in Gutiérrez's seaside hometown in Spain led to long days indoors, where she found a science television show that inspired an entire life of education and research that eventually brought her to Salk. Today, she works in Professor Susan Kaech's lab studying Alzheimer's disease.

Irene López Gutiérrez: After every storm comes sunshine—and scienceRainy winter weather in Gutiérrez's seaside hometown in Spain led to long days indoors, where she found a science television show that inspired an entire life of education and research that eventually brought her to Salk. Today, she works in Professor Susan Kaech's lab studying Alzheimer's disease. Michelle Chamberlain named Salk’s new Vice President of External RelationsMichelle Chamberlain assumed the role on April 2, where she will serve on Salk's Executive Leadership Team and oversee all fundraising efforts, communications, community engagement, education outreach programs, foundation relations, and stewardship activities.

Michelle Chamberlain named Salk’s new Vice President of External RelationsMichelle Chamberlain assumed the role on April 2, where she will serve on Salk's Executive Leadership Team and oversee all fundraising efforts, communications, community engagement, education outreach programs, foundation relations, and stewardship activities. Trustee Richard A. Heyman donates $4.5 million to enable early-stage innovative researchRichard A. Heyman, a member of the Salk Institute’s Board of Trustees, and his wife, Anne Daigle, have donated $4.5 million to establish the new Richard A. Heyman Collaborative Innovation Fund to support Institute faculty on collaborative, early-stage studies aimed at big, bold questions.

Trustee Richard A. Heyman donates $4.5 million to enable early-stage innovative researchRichard A. Heyman, a member of the Salk Institute’s Board of Trustees, and his wife, Anne Daigle, have donated $4.5 million to establish the new Richard A. Heyman Collaborative Innovation Fund to support Institute faculty on collaborative, early-stage studies aimed at big, bold questions. 50 years of discovery: Professor Tony Hunter’s half-century legacy at SalkTony Hunter first arrived at the Salk Institute in 1971 as a postdoctoral trainee from the University of Cambridge. Four years later, he officially joined the Institute as an assistant professor and cancer biology pioneer.

50 years of discovery: Professor Tony Hunter’s half-century legacy at SalkTony Hunter first arrived at the Salk Institute in 1971 as a postdoctoral trainee from the University of Cambridge. Four years later, he officially joined the Institute as an assistant professor and cancer biology pioneer.