Insights Kay Watt From Peace Corps to plant science

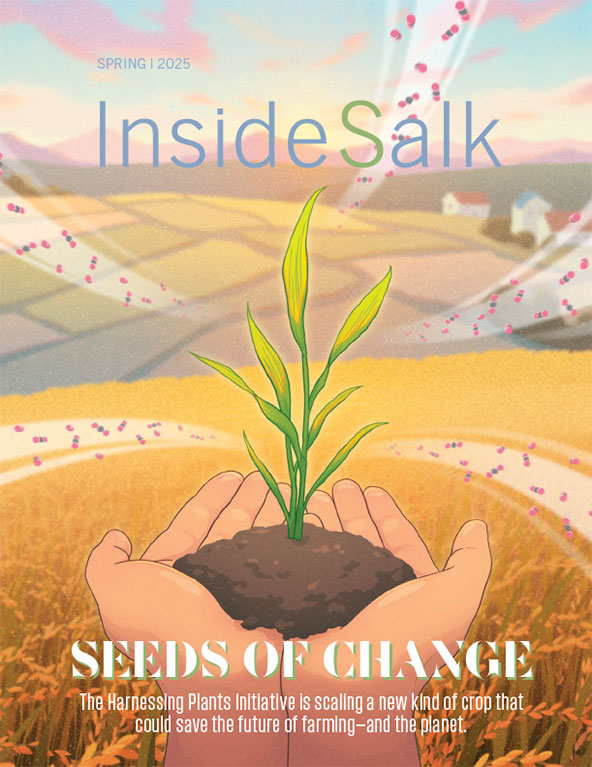

Salk has long been known as the place where cures begin. But in recent years, it’s also become a source of sustainable climate solutions. Through the Harnessing Plants Initiative, Salk scientists are optimizing crop and wetland plants to pull more carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and better withstand the effects of climate change.

At the heart of the Harnessing Plants Initiative is Program Manager Kay Watt. She’s a geneticist and plant biologist by training, but Watt isn’t doing the experiments herself these days. Instead, she tackles all of the strategy, site operations, budgeting, reporting, communication, and outreach that keep the whole program on track.

“We have incredible scientists on our team, but my job is to figure out how to get their great science out of the lab and into the world,” Watt says.

This practical mindset comes from her years on the frontlines of food and agriculture, where she witnessed the real impact that heat, drought, and infectious disease can have on farms and farmers.

But long before she worked in the forests of Panama or the fields of California, Watt was getting her hands dirty in the garden at her family’s Massachusetts home.

“As soon as I could walk, I was picking up a hoe or a rake and trying to help,” she recalls. But as a child, Watt had yet to appreciate the relationship between gardening and science. Spending time in nature was just a part of her family’s way of life.

“One thing that really stands out to me from my childhood is the beautiful red cardinals that we’d see in the wintertime,” she says. “The sky would be cloudy, the trees would all be dormant, the ground would be blanketed with snow, and in all this monochrome, you’d see these beautiful bright flashes of color. They were one of my favorite animals to see when we’d go out for walks in the woods.”

But it’s not the beauty of this wintry scene that stands out to her now. It’s what she didn’t know at the time: cardinals are not native to New England. Only in the past few decades had the birds started coming up the coast and populating the warming North. This symbol of her idyllic 1980s upbringing was actually a sign that climate change was already well underway.

“It really struck me to learn that,” Watt says. “Reflecting back and realizing that experience was due to climate change was very humbling.”

After graduating college with a degree in philosophy and religious studies, Watt’s desire to do good led her to join the Peace Corps. While on assignment in Panama, she was tasked with helping local coffee farmers learn new agricultural techniques for reducing the spread of crop-killing pathogens.

“Every plant counts when you’re a farmer living season-to-season off of your harvest,” she says, referring to the subsistence farmers who make up a quarter of the world’s population. “Their entire livelihoods depend on agriculture, but the crop varieties they’re growing aren’t strong enough against disease and environmental stressors to sustain their food supply.”

Watt wasn’t just learning about food scarcity in a lecture hall—here, she was experiencing it firsthand. There were no cars or highways in the village she was living in, only horses and dirt roads. There was no constant stream of new goods coming into town, not a single delivery truck in sight. To eat, there was rice. To drink, there was rainwater. When night fell, kerosene lanterns were the only source of light.

“It made me very aware of how much I didn’t know and hadn’t experienced in my life,” Watt says. She describes her return to the United States as “a massive culture shock.”

“I would go to Whole Foods and spend several hours just looking at all the products because it was completely unimaginable to have that amount of variety available to you at all times.”

It was then that she made two life-changing decisions: She was going to dedicate her career to improving global food security, and she would use plant and agricultural science to do it.

Within two years of intensive studying, Watt completed a second bachelor’s degree in plant biology and was on her way to getting a PhD in genetics. While in graduate school, she used modern plant breeding techniques to develop new drought-resistant varieties of chickpeas.

“I thought California farmers would be especially excited to grow a heartier chickpea crop that didn’t require as much water,” she says. “But it turns out there wasn’t much financial incentive for growers to use less water because of how the irrigation policies were set up.”

After five years of painstaking work, her chickpea plant was deemed scientifically successful but commercially unviable.

“I realized then that a lot of smart people were concentrated on the science, but they weren’t necessarily looking at all the other factors that can influence the application of that science in the real world,” Watt says. “I decided I would focus on that moving forward.”

Watt has been an integral part of Salk’s Harnessing Plants Initiative since 2022. While its researchers continue optimizing the science of Salk Ideal Plants®, she skillfully oversees the strategy and logistics of getting them into public use.

“We’re now at the exciting stage of advancing our first Salk Ideal crops into field trials,” she says. “It’s a major milestone for the program, so I’m optimistic that we’ll soon see these plants moving beyond our greenhouses to support farms and farmers around the globe.”

Kay Watt | Beyond Lab Walls Podcast

Hear how Kay’s experiences have motivated her to become a plant geneticist and program manager, supporting the fight against climate change through Salk’s Harnessing Plants Initiative.

Featured Stories

Connecting the dots—From the immune system to the brain and back againBy collaborating across disciplines like genetics, neuroscience, and immunology, Salk scientists are uniquely positioned to lead us into a future of healthier aging and effective therapeutics for Alzheimer’s.

Connecting the dots—From the immune system to the brain and back againBy collaborating across disciplines like genetics, neuroscience, and immunology, Salk scientists are uniquely positioned to lead us into a future of healthier aging and effective therapeutics for Alzheimer’s. Salk mourns the loss of Joanne ChorySalk Professor Joanne Chory, one of the world’s preeminent plant biologists who led the charge to mitigate climate change with plant-based solutions, died on November 12, 2024, at the age of 69 due to complications from Parkinson’s disease.

Salk mourns the loss of Joanne ChorySalk Professor Joanne Chory, one of the world’s preeminent plant biologists who led the charge to mitigate climate change with plant-based solutions, died on November 12, 2024, at the age of 69 due to complications from Parkinson’s disease.  Talmo Pereira—From video game bots to leading-edge AI toolsTalmo Pereira is a Salk Fellow, a unique role that empowers scientists to move straight from graduate school to leading their own research groups without postdoctoral training.

Talmo Pereira—From video game bots to leading-edge AI toolsTalmo Pereira is a Salk Fellow, a unique role that empowers scientists to move straight from graduate school to leading their own research groups without postdoctoral training. Kay Watt—From Peace Corps to plant scienceAt the heart of the Harnessing Plants Initiative is Program Manager Kay Watt who tackles all of the strategy, site operations, budgeting, reporting, communication, and outreach that keep the whole program on track.

Kay Watt—From Peace Corps to plant scienceAt the heart of the Harnessing Plants Initiative is Program Manager Kay Watt who tackles all of the strategy, site operations, budgeting, reporting, communication, and outreach that keep the whole program on track.  Pau Esparza-Moltó—Seeing mitochondria as more than just a powerhousePau Esparza-Moltó, a postdoctoral researcher in Professor Gerald Shadel’s lab, finds comfort in the similarities between his hometown in Spain and San Diego, where he now studies cell-powering mitochondria.

Pau Esparza-Moltó—Seeing mitochondria as more than just a powerhousePau Esparza-Moltó, a postdoctoral researcher in Professor Gerald Shadel’s lab, finds comfort in the similarities between his hometown in Spain and San Diego, where he now studies cell-powering mitochondria. Salk summer programs bring equity and opportunity to the STEM career pipelineThe Salk Institute recently hosted two inaugural events designed to enhance diversity within the scientific community: the Rising Stars Symposium and the Diverse Inclusive Scientific Community Offering a Vision for an Ecosystem Reimagined (DISCOVER) Symposium.

Salk summer programs bring equity and opportunity to the STEM career pipelineThe Salk Institute recently hosted two inaugural events designed to enhance diversity within the scientific community: the Rising Stars Symposium and the Diverse Inclusive Scientific Community Offering a Vision for an Ecosystem Reimagined (DISCOVER) Symposium.