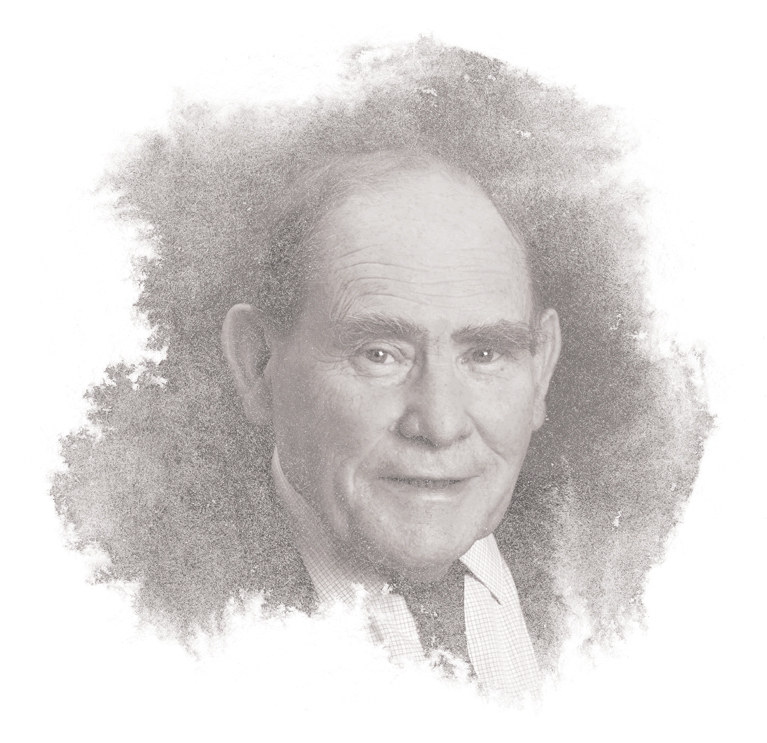

IN MEMORIAM

Nobel Laureate and Salk Distinguished Professor Emeritus Sydney Brenner passed away on April 5, 2019, in Singapore, at the age of 92. Over the course of six decades, Brenner shaped the modern understanding of the genetic code.

“We at Salk join countless other scientists and researchers around the world in mourning the passing of Sydney Brenner,” says Salk President Rusty Gage. “Along with raising the field of molecular biology to maturity, Sydney was a generous and dedicated mentor, colleague and friend. He was an inspiration to generations of scientists, and he will be greatly missed.”

“We all owe much to Sydney. With his passing, we have lost a great scientist and a good friend,” says Salk Professor Terrence Sejnowski.

“Sydney Brenner was a luminary, a ‘once in a lifetime’ scientist. We at the Salk Institute were entertained and enthralled by his wit and wisdom,” adds Salk Professor Ronald Evans. “His research inspired my career. He will be remembered in perpetuity for his brilliant discoveries that ushered in a new era of science and a new generation of scientists.”

Brenner joined the Institute as a Distinguished Professor in 2000 and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2002, along with H. Robert Horvitz and John Sulston, for “discoveries concerning genetic regulation of organ development and programmed cell death,” according to the Nobel Foundation. The team pioneered research using the translucent microscopic worm Caenorhabditis elegans as a model system for linking genetics, cell division, organ formation and cell death. Their discoveries laid the groundwork for making C. elegans a major model organism in research. Today, thousands of researchers use C. elegans for their studies, and Brenner was honored in 2007, when a closely related nematode—C. brenneri—was named after him.

Over the course of six decades, Brenner shaped the modern understanding of the genetic code.

Born in Germiston, South Africa, in 1927, Brenner earned degrees in medicine and science from Johannesburg’s University of Witwatersrand in 1947 before moving to Oxford University in 1952 to pursue his PhD in physical chemistry. While at Oxford, he became engrossed in DNA and developmental genetics research. He joined the University of Cambridge in 1956 and shared an office with future Nobel Laureate Francis Crick for nearly 20 years.

In 1961, in partnership with Crick, Brenner demonstrated that the genetic code for proteins uses a series of three nucleotides to code for a single amino acid. He further showed that certain combinations of triplet nucleotides called “nonsense” or “stop” codons (a phrase he coined) halt protein creation during translation.

Around this time, Brenner also co-discovered the existence of messenger RNA (mRNA), one of the molecular intermediates between DNA and proteins, and demonstrated that the nucleotide sequence of mRNA determines the order of amino acids in proteins. This work led to his first Lasker Award in Basic Medical Research; he later received a second Lasker Award in honor of his outstanding lifetime achievements.

In 1976, Crick left Cambridge to join the Salk Institute, and Brenner joined him once again, in 1981, as a nonresident fellow. In 1992, Brenner was appointed to the Scripps Research Institute, located less than a mile from Salk. Brenner and Crick were reunited at Salk in 2000. In 2001, Brenner coauthored an autobiography titled, My Life in Science. He also helped to establish a number of scientific institutes, including in Japan and Singapore.

“Sydney was a dear friend and uber-mentor,” says Gene Yeo, a former researcher at Salk and a professor at UC San Diego, who worked with Brenner (and whose father, Philip Yeo, developed with Brenner a number of scientific institutes in Singapore). “We will miss him terribly.”

Brenner is survived by his children Belinda, Carla and Stefan.

A tribute to Audrey Geisel 1921 – 2018

The Salk Institute and the greater San Diego community lost a good friend late last year. Audrey Geisel, the fun-loving, dedicated philanthropist who was a founding Symphony donor and attended every year until the last few due to declining health, passed away at age 97 on December 19, 2018.

Born Audrey Stone in Chicago on August 14, 1921, she went on to graduate from Indiana University and have an early career as a nurse. Geisel and her first husband, Dr. E. Grey Dimond, and their two daughters moved to San Diego in 1960.

She later married Theodor Geisel, more famously known as Dr. Seuss, in 1968.

Geisel was a generous supporter of numerous charitable organizations and causes. She and Theodor Geisel were long-time La Jolla residents who valued art and ventures that benefitted humanity. There is no better evidence of the latter than her creation of the Audrey Geisel Chair in Biomedical Science, established at Salk in 2012, which was first held by Professor Edward Callaway and is now held by Professor Gerald Shadel.

“She was a generous person with a warm and loving soul,” says Rebecca Newman, Salk’s vice president of External Relations. “She did so much for the Institute that we would not have been able to accomplish otherwise and her imprint on our success will be seen for years to come. She only supported institutions she truly believed in, so it is a real honor for Salk to count her as one of our great benefactors.”

Geisel, who was friends with Institute founder Jonas Salk and his wife, famed artist Françoise Gilot, cherished her support of Salk. She was a founding donor to the President’s Club and founding member, in 1978, of the Women’s Association of the Salk Institute, which helped increase awareness about the importance of basic research and provided support for the Salk Scholars Fund.

“One thing that she hated to miss was a good party and the Symphony at Salk is one of the great ones,” says Judith Morgan, a Salk supporter, friend of Geisel and author of Dr. Seuss and Mr. Geisel. “I shall miss her.”

Longtime Salk supporters Irwin and Joan Jacobs agree, sharing that it was always special to see Geisel at Symphony.

“We met Audrey shortly after we came here in 1966 and it was a pleasure to be with her because she had such a bubbly and welcoming personality,” Salk Trustee and Board Chair Emeritus Irwin Jacobs says. “It was always fun to meet her at Symphony at Salk and talk about the music.”

In addition to supporting Salk, she gave to other local organizations including UC San Diego (the main campus library is named for Audrey and Theodor Geisel), The Zoological Society of San Diego, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, the La Jolla Playhouse and the Old Globe Theatre, among many others.

“I had the wonderful experience of working with Audrey and Ted Geisel for over forty years,” says Claudia Prescott, Dr. Seuss Foundation president. “They meant a great deal to me and I learned so much working side by side with them.”

A thoughtful and conscientious donor, Geisel met regularly with her associates. Karen and Don Cohn (a Salk trustee) recall Geisel’s notoriously early breakfast meetings fondly, noting how Geisel would pull up in her Cadillac—complete with personalized “Grinch” license plates—to conduct business at one of La Jolla’s iconic restaurants.

“You would meet her at 7:30 a.m. and had to have a pink grapefruit and breakfast before conducting business,” Karen Cohn says. “Then you would make your request to her and she would usually say yes. It was always an honor to have her involved in a project.”

“Audrey was such a strong force, with a great sense of humor,” Don Cohn adds. “She had a purpose and she exercised it beautifully.”

Geisel’s positive nature and advocacy for the arts and sciences ensures that her influence lives on—both in San Diego and beyond.

Support a legacy where cures begin.

Featured Stories

Kay Tye – Breaking down the brainKay Tye, the newest addition to Salk’s faculty, is a burst of energy who can chat about everything from the mysteries of the brain to the intricacies of a breakdance move. In this Q&A, she discusses her roundabout journey to science, her passion for mentorship and her love of life outside the lab.

Kay Tye – Breaking down the brainKay Tye, the newest addition to Salk’s faculty, is a burst of energy who can chat about everything from the mysteries of the brain to the intricacies of a breakdance move. In this Q&A, she discusses her roundabout journey to science, her passion for mentorship and her love of life outside the lab. How to stop a killerPancreatic cancer is one of the most difficult cancers to detect and treat, in part because of an impenetrable "shield" that forms around the tumor. Salk scientists, many of whom have a personal connection to cancer, are leading the charge in new approaches to tackle this deadly disease.

How to stop a killerPancreatic cancer is one of the most difficult cancers to detect and treat, in part because of an impenetrable "shield" that forms around the tumor. Salk scientists, many of whom have a personal connection to cancer, are leading the charge in new approaches to tackle this deadly disease. Travis Berggren – Working at the intersection of biology and technologySenior Staff Scientist Travis Berggren shares his path to Salk and his perspective on how advances in technology facilitate world-changing discoveries in genetics, neuroscience, cancer, immunology, plant biology and other areas.

Travis Berggren – Working at the intersection of biology and technologySenior Staff Scientist Travis Berggren shares his path to Salk and his perspective on how advances in technology facilitate world-changing discoveries in genetics, neuroscience, cancer, immunology, plant biology and other areas.