The unexpected collaboration started with a phone call.

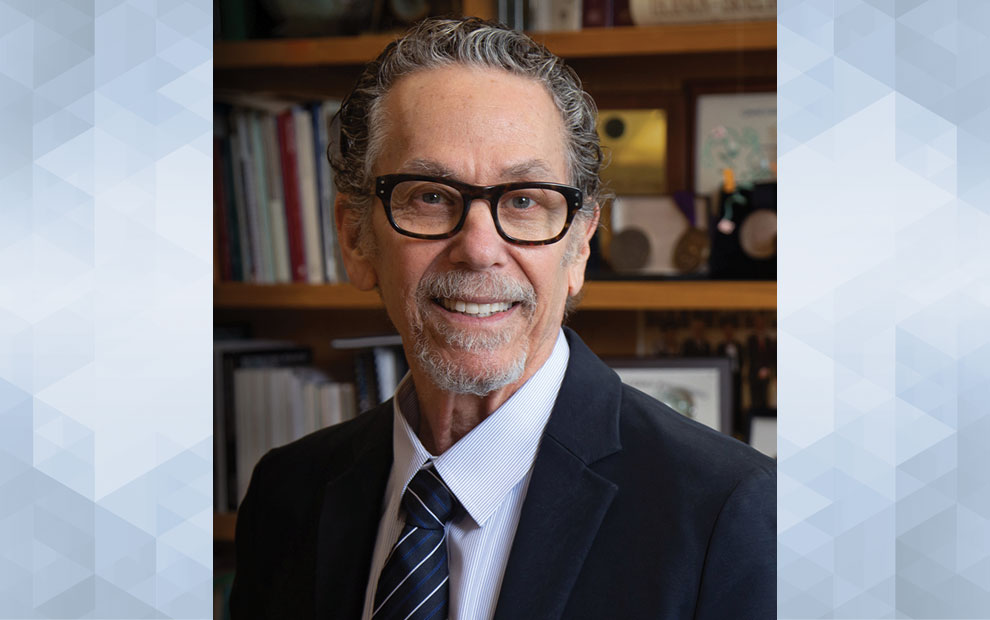

A few years ago, Salk American Cancer Society Professor Tony Hunter was catching up with his older son, Sean, who at the time was a new graduate student in the cancer biology program at Stanford University. Sean had recently joined a lab led by bioengineering Professor Jennifer Cochran and wanted his dad’s opinion about a research project he might pursue.

In 2015, Sean had attended a talk by cancer researcher Frank McCormick about his work on a protein made and exported by pancreatic cancer cells called leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). LIF is a powerful cytokine (a type of protein) that signals cells to adopt a primitive, less differentiated state and could be a promising target for treating cancer. For his project, Sean told his father, he was proposing to engineer proteins to inhibit LIF function.

“And I nearly fell off my chair when he said that, because, unbeknownst to Sean, my lab had been working on this same protein in pancreatic cancer for several years,” Hunter says. “And I said ‘yes, of course I think it would be a great project for you because we think it’s a great project too!’” A few years later, in 2019, Hunter’s lab at Salk reported the results of their work showing how LIF is involved in pathways that drive pancreatic cancer progression and could be blocked by an antagonist antibody to slow pancreatic cancer progression in a mouse model—a discovery that points to LIF as a potentially useful therapeutic target as well as a biomarker to help diagnose the disease more efficiently.

Hunter and his son decided to team up for the next step in their next investigation: Using protein engineering, Sean designed a therapeutic protein that could bind tightly to LIF and sequester it. Then, using a mouse model of pancreatic cancer developed in Hunter’s lab, the researchers tested the new therapy and found that it indeed blocked LIF signals involved in pancreatic cancer. They published their work in the journal Communications Biology on April 12, 2021. The publication marks the Hunters’ first formal research collaboration.

“It obviously is very exciting to be able to publish a paper with Sean,” Hunter says. “He’s turned out to be an excellent scientist and he knows what he’s doing … It’s been great working with him.”

Before this collaboration, Sean got his introduction to running experiments in his dad’s Salk lab, volunteering there for three summers during high school before building on his scientific education as an undergraduate and in graduate school. Sean’s path to science was inspired by his parents, both of whom are biologists.

While the son has moved toward translational research and the father remains focused on basic science, both are continuing to pursue new avenues to treat cancer.