In Memoriam

A trailblazer’s lasting legacy:

Ursula Bellugi bridged humanity and science

Last spring, the world lost a true trailblazer.

Bellugi, Distinguished Professor Emerita and Founder’s Chair at the Salk Institute, 2008 inductee to the National Academy of Sciences and winner of the Jacob Javits Neuroscience Investigator Award, passed away peacefully on April 17, 2022, in La Jolla, at the age of 91.

She was predeceased by her husband Edward S. Klima and her son David Bellugi. She is survived by her son Rob Klima, her sister Ruth Rosenberg, her brother Hans Herzberger, and by four grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

“The entire Salk community is grieved by the loss of Ursula Bellugi,” says Salk President Rusty Gage. “She leaves an indelible legacy of shedding light on how humans communicate and socialize. The humanity and compassion she brought to her work were truly special, and we all will miss her dearly.”

Ursula Bellugi (third from right) stands among her peers in the Courtyard of the Salk Institute, 1984

A World-class Scientist

Bellugi’s contributions to our understanding of the role biology plays in communication are virtually unparalleled; she is widely regarded as the founder of the neurobiology of American Sign Language (ASL). She was the first to demonstrate that ASL is a true language. She studied its neurological facets extensively, leading to the discovery that the same areas of the human brain that specialize in spoken language are activated by sign language—a striking demonstration of neuronal plasticity. This work also provided significant insights into how the brain learns and interprets (and even forgets) language.

“She and my father were able to prove American Sign Language was a real language, with all of the syntax and grammar as spoken language,” her son Rob Klima says. “My mother’s contributions opened a lot of doors for Deaf people and allowed them a chance to flourish like they never had before. Before her work, Deaf people were discouraged from signing. They were pushed to assimilate, as it was thought that signing was pantomime or a cheap substitute for spoken language.”

“Her work with her husband was absolutely foundational. What she did with sign language turned the science upside down and sideways,” says Rachel Mayberry, a professor in the Department of Linguistics at UC San Diego. Mayberry worked in Bellugi’s lab during the summer of 1973 and considers Bellugi a role model. “People forget that most professors at that time were males. Here was a woman who was really interested in children but was also a top-flight researcher. I had never seen anything like her before.”

Not content to remain a pioneer of one foundational area of research, Bellugi pivoted her focus in 1981 to an untapped field of research: Williams syndrome. Meeting a young San Diego girl with Williams syndrome piqued her curiosity about the condition.

Williams syndrome is a genetic condition present at birth that affects an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 people in the US. It is characterized by a number of health issues, including cardiovascular disease, developmental delays and learning challenges. Children with Williams syndrome tend to be particularly social and friendly, according to the Williams Syndrome Association.

Bellugi leveraged her expertise to better understand Williams syndrome and autism, two conditions that affect social behaviors in opposite ways. Through her use of advanced imaging technologies, Bellugi was able to visualize how related gene deletions alter brain activity, map the affected neural circuits and develop stem cell reprogramming techniques to reveal the biological basis of these drastically different disorders.

Today, Bellugi is widely regarded as pioneering the study of Williams syndrome.

“We didn’t limit ourselves to anything,” Bellugi said in a 2018 video recorded by the Williams Syndrome Association. “We wanted to know everything about Williams syndrome… The most important thing we found is that Williams syndrome holds keys to some of the most basic questions about what it means to be human.”

Ursula and husband Edward Klima (provided by Rob Klima)

Early Life and Journey to Salk

Bellugi was born in Jena, Germany (about 45 miles southwest of Leipzig) on February 21, 1931, to Max and Edith Herzberger. Her family immigrated to the United States when Bellugi was young, fleeing Germany in 1934 on the encouragement of Albert Einstein, Max’s friend and former teacher in Berlin, as Hitler was rising in power. Bellugi’s father took a job at Eastman Kodak’s optical research laboratories, a job arranged for him by Einstein.

Bellugi attended Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, majoring in psychology and graduating in 1952.

In 1953, she married Italian composer and conductor Piero Bellugi. The couple had two boys, Rob and David, but divorced in 1959. Bellugi then moved with her sons to Rochester, New York, to live with her parents.

Rob Klima describes the period of his mother’s life that followed as “hard times.” The small family bounced around the country, living with various relatives for several years. Then, Bellugi moved them to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to attend Harvard University, where she would go on to earn her Doctorate of Education in 1967, all the while raising her sons as a single mother. Shortly after completing her PhD, she became an associate professor at Harvard.

It was during this time Bellugi met and married linguist Edward S. Klima, who would adopt her sons. The new family moved to La Jolla, California, where Klima took a teaching position at UC San Diego and Bellugi began working at the Salk Institute in 1968. Two years later she was named director of Salk’s Laboratory for Cognitive Neuroscience.

“That was a really wonderful time,” Rob Klima says. “My brother and I hated the bitter cold of the Northeast; and then we went to living above Black’s Beach. It was really the best place to grow up.”

“Jonas Salk actually asked me to set up a little lab [at the Salk Institute],” Bellugi said in the Williams Syndrome Association video. “I was the only one working with people directly. I’ve always been fascinated with language. At the time, nobody thought there was anything like language among Deaf people. We discovered and uncovered the particular languages that Deaf people invented on their own, and they were languages of the hand and in the eyes.”

From left: Ursula Bellugi’s mother, Edith Herzberger, Ursula and Francis Crick (provided by Rob Klima)

A People Person

Affectionately referred to as “Ursie” by many closest to her, including colleagues, lab workers and students, Bellugi loved people, a quality that shone through in every facet of her life.

“Ursula had a real passion for people,” says Professor Joanne Chory, who joined Salk in 1988 and got to know Bellugi well over the years. “She was such a sweetie.”

While most Salk labs focus on preclinical work in test tubes, Petri dishes and animal models, Bellugi was one of the first researchers to include people in her studies. In addition, she hired many Deaf researchers to work in her lab over the years.

Beyond the lab, she was always sure to embrace the human side of her work. She held annual gatherings for children with Williams syndrome who participated in her studies. The events were eagerly anticipated by researchers and participants alike.

On one such occasion in 2001, actor Alan Alda visited the Salk campus and filmed an episode of a television program called Scientific American Frontiers, highlighting Bellugi and her work with children with Williams syndrome, who gathered for a picnic on the Institute’s north lawn. In the video, children can be seen playing lawn games, receiving prizes, carrying balloon animals and simply enjoying everyone’s company.

Simple efforts such as these were Bellugi’s way to ensure that any work conducted at Salk was grounded in the people who made it possible.

“She loved being around people and took every opportunity to get to know them on both a personal and professional level,” Klima says. “Whether they were colleagues at the Salk Institute or people she encountered at her weekly hairdresser appointment, she loved interacting with people and becoming a part of their lives.”

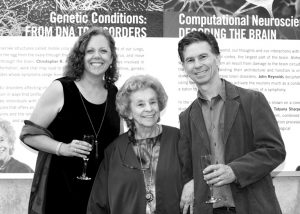

From left: MaryAnn Klima, Ursula Bellugi and Rob Klima

An Inspirational Mentor

Her love of people also informed her role as a mentor. Bellugi’s contributions to science can’t be fully told without acknowledging the profound impact she made on her students and lab workers.

“As an academic mentor and research leader, Ursula contributed to evolutionary thinking in linguistics, neuropsychology and biology. She inspired all of us to stretch to our limits,” says Robbin M. Battison, who was a graduate student in Bellugi’s lab from 1970 to 1973.

“I learned from watching Ursie work that you can’t be afraid of what you don’t know. You have to embrace it,” Rachel Mayberry says.

Bellugi’s supportive nature extended beyond students and her lab workers. Her colleagues recount how inspiring she was to them as well.

“Ursula was really sweet to me,” says Chory, adding that she appreciated Bellugi. “She was like me. She lived under the radar, and when you work that way, you can do whatever you want. We bonded over that.”

Virologist and Salk alum Matthew Weitzman considered Bellugi a treasured friend and mentor.

“Our science was very different, but she always wanted to grasp what I was working on or find out what the driving question of the research was,” says Weitzman, who was a member of Salk’s faculty with Bellugi from 1997 to 2011. “After everyone else had left faculty lunch on Fridays, we would linger behind and chat about science, careers, family and philosophy. She would ask probing and insightful questions. She was always interested in the larger implications of our work.”

Ursula Bellugi with her lab team, 2014

Award-Winner

Bellugi authored numerous books and was a much sought-after speaker on the subjects of neurobiology, language and other topics. The Signs of Language, published in 1979 and written with her late husband Edward Klima and several colleagues, is considered a seminal publication on the grammar and psychology of signed language. It is still taught in university linguistics programs today.

In addition to the Javits Neuroscience Investigator Award, Bellugi was the recipient of numerous awards recognizing her contributions to linguistics and neurobiology. These included being elected to the National Academy of Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She was honored with two MERIT awards from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, a Woman of the Decade Award from the City of Los Angeles and a Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award from the American Psychological Association.

In 2019, the Salk Women & Science Trailblazer Award was renamed in honor of Bellugi, who established an endowed fund to support those who have pioneered changes within STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art and mathematics) fields. The Ursula Bellugi Trailblazer Award recognizes outstanding achievements made by women in their fields. (See this issue’s Events section to learn about the latest award recipient.)

A Passion for Work and Salk

Even as she aged, Bellugi never lost her ability to derive happiness from her work. When, in the course of a 2015 interview by the San Diego Union-Tribune, she was asked why she had continued to work well into her eighties, she “cocked her head, as if to say, ‘are you really asking me why I still have a lab at 84?’” Her answer to the question summed up her attitude toward research: “My work is a joy,” she said, “I have a passion for this. I don’t know how to explain it any other way.”

Bellugi retired and closed her Salk lab in 2018, at the age of 87, but her curiosity and love for research never waned. Rob Klima says she enjoyed being at the computer, where she loved to email friends and colleagues. Even when her health declined to the point of needing to remain in bed, Klima set her up with an iPad so she could remain plugged in.

“She had an incredibly curious mind. Always wanting to learn, always wanting to research,” Klima says.

Another thing she loved to do was stay informed about Salk happenings. She read issues of Inside Salk and anything else Salk-related she could find.

Joanne Chory shares that one of her fondest Bellugi memories is how Bellugi would proudly show off a photo she kept on her phone of herself, her mother, and Nobel laureate and Salk faculty member Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA.

“The love of her life, other than her family, was the Salk Institute,” Klima says. “Salk gave her an opportunity and she ran with it.”

Support a legacy where cures begin.

Featured Stories

What’s so special about Salk? Everything.An exceptional history, visionary design and trailblazing faculty make the Salk Institute unique among elite research institutions. And we’re just getting started. Today, Salk faculty are daily making discoveries that may one day turn the tide on Alzheimer’s, aging, cancers, climate change and more.

What’s so special about Salk? Everything.An exceptional history, visionary design and trailblazing faculty make the Salk Institute unique among elite research institutions. And we’re just getting started. Today, Salk faculty are daily making discoveries that may one day turn the tide on Alzheimer’s, aging, cancers, climate change and more. Margarita Behrens—Master of brain circuitsGrowing up in Chile, Research Professor Margarita Behrens was torn between becoming an architect and a scientist. She ultimately decided to pursue biochemistry. Now at Salk, Behrens studies how neurons develop in the brain. Her findings have implications for neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia and autism.

Margarita Behrens—Master of brain circuitsGrowing up in Chile, Research Professor Margarita Behrens was torn between becoming an architect and a scientist. She ultimately decided to pursue biochemistry. Now at Salk, Behrens studies how neurons develop in the brain. Her findings have implications for neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia and autism.

Julie Auger—Shaping Salk’s science through shared resourcesJulie Auger’s mother was at a conference in the mid-1980s when she met Jonas Salk. She got his autograph and mailed it to Auger with a note saying, “Don’t ever stop trying to achieve your dreams.” Auger took her mom’s advice, and today she is the executive director of Research Operations at the Salk Institute.

Julie Auger—Shaping Salk’s science through shared resourcesJulie Auger’s mother was at a conference in the mid-1980s when she met Jonas Salk. She got his autograph and mailed it to Auger with a note saying, “Don’t ever stop trying to achieve your dreams.” Auger took her mom’s advice, and today she is the executive director of Research Operations at the Salk Institute. Gaurav Mendiratta— Using math to solve cancerJumping from theoretical physics to cancer research with no prior training in biological sciences wasn’t an easy transition for Gaurav Mendiratta. Couple this with a move across the world and the birth of his first child shortly after starting his postdoctoral training in a newly opened laboratory—Mendiratta had his work cut out for him.

Gaurav Mendiratta— Using math to solve cancerJumping from theoretical physics to cancer research with no prior training in biological sciences wasn’t an easy transition for Gaurav Mendiratta. Couple this with a move across the world and the birth of his first child shortly after starting his postdoctoral training in a newly opened laboratory—Mendiratta had his work cut out for him. A trailblazer’s lasting legacy: Ursula Bellugi bridged humanity and scienceDespite being a world-renowned, award-winning scientific pioneer, Distinguished Professor Emerita Ursula Bellugi didn’t like to say she was smart. Instead, she credited her tremendous success to her insatiable curiosity and her willingness to ask the right questions. This past spring, the world lost a true trailblazer.

A trailblazer’s lasting legacy: Ursula Bellugi bridged humanity and scienceDespite being a world-renowned, award-winning scientific pioneer, Distinguished Professor Emerita Ursula Bellugi didn’t like to say she was smart. Instead, she credited her tremendous success to her insatiable curiosity and her willingness to ask the right questions. This past spring, the world lost a true trailblazer.