Considered a pioneer in neuroscience, Distinguished Professor Emeritus Charles F. Stevens died peacefully on October 21, 2022, at his home in San Diego. He was 88.

Stevens joined Salk in 1990, after serving as a faculty member at the University of Washington School of Medicine and Yale School of Medicine. He was also a research scientist and advisory board member with the Kavli Institute for Brain and Mind at UC San Diego. He remained on Salk’s faculty until 2018.

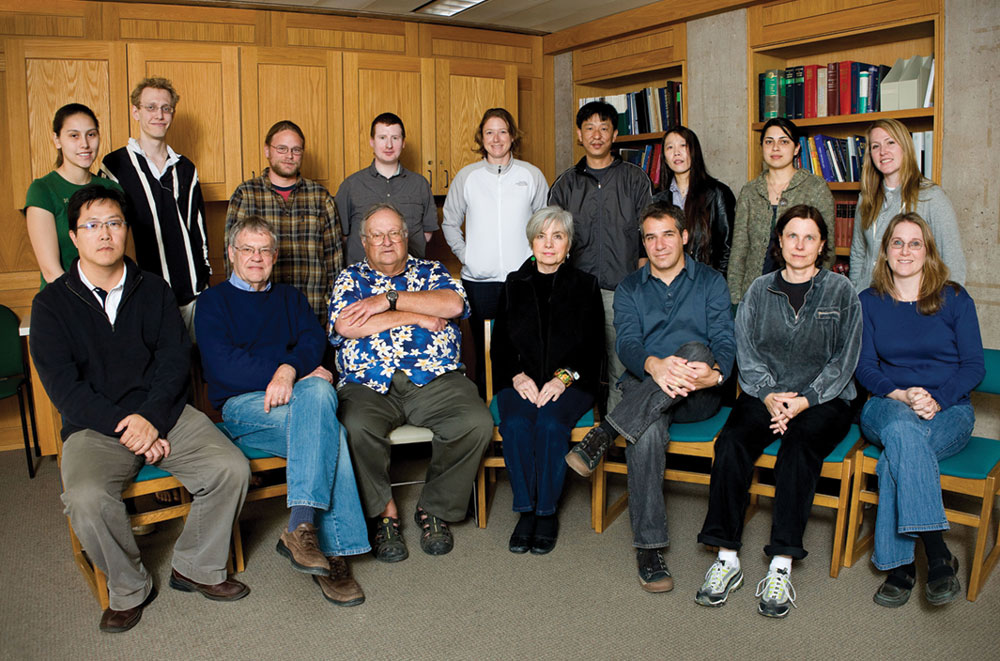

Top row from left: Amanda Vlasveld, Bayle Shanks, Joe Snider, Ruadhan O’Flanagan, Corinne Teeter, Jian Yu, Yongling Zhu, Carol Glogowski, Tresa McGranahan; Bottom row from left: Hosuk Lee, Chuck Stevens, Steve Heinemann, Jane Jenerette, Gustavo Dziewczapolski, Conny Maron, Jenn Greenhall. February 2009.

“Chuck was a giant in modern neuroscience,” says Salk President Rusty Gage. “He pioneered many techniques to study how messages are transmitted across synapses in the brain and how these signals help us learn and remember. He always brought unique perspectives to any problem and inspired us all to think more creatively. But what’s more, he always had time to talk with his colleagues and trainees, many of whom went on to become accomplished neuroscientists themselves. He will be missed.”

Stevens was responsible for confirming via modern experimentation long-held beliefs regarding the consistency of neuron density throughout the brain. He was also a leader in exploring and understanding the scalable architecture of the brain, which centers on the idea that something can gain more properties simply by becoming bigger.

Stevens worked to formulate a complete list of the principles that govern organization in the brains of a wide variety of animals, from simple creatures to humans. He sought to know how scalable architecture is enforced in the brain and if there are always constant ratios between the sizes of cells and structures.

To answer these fundamental questions, Stevens pinpointed the scaling laws that govern how brains grow and develop. He observed how organisms develop from an embryo to an adult using goldfish as a model organism. Unlike mammals, goldfish have brains that continue to grow throughout their adult lives. Stevens unearthed several design rules of the goldfish brain, such as set relationships between certain brain areas and laws on how neurons leading from the eyes to the brain are organized. He charted how those rules are enforced during development and growth.

Stevens was born on September 1, 1934, in Chicago, Illinois, to Russell Stevens and Reba Hoffman Stevens.

Stevens with wife, Jane, enjoying the Salk Courtyard.

He married Jane Robinson on June 18, 1956, shortly after he graduated from Harvard College and she graduated from Wellesley College. He was the first person in his family to receive a bachelor’s degree.

After earning his Bachelor of Arts degree in psychology from Harvard, Stevens received an MD from Yale University and a PhD in biophysics from the Rockefeller Institute. He was elected to membership in the National Academy of Sciences in 1982 and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1984. He was formerly a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and adjunct faculty member in the UC San Diego School of Medicine department of pharmacology. He was awarded the National Academy of Sciences’ Award for Scientific Reviewing in 2000.

Stevens is survived by his wife, Jane R. Stevens; their daughters Katharine B. Stevens of Washington, DC, and Alexandra Stevens Thomas of Madison, Wisconsin; and three grandchildren. He was preceded in death by a daughter, Margaret R. Stevens O’Neill.

In memory of Stevens, his family welcomes donations to the Charles F. Stevens Memorial Neuroscience Research Award at the Salk Institute, which was established to provide research grants to graduate students working in the field of neuroscience at UC San Diego and the Salk Institute.