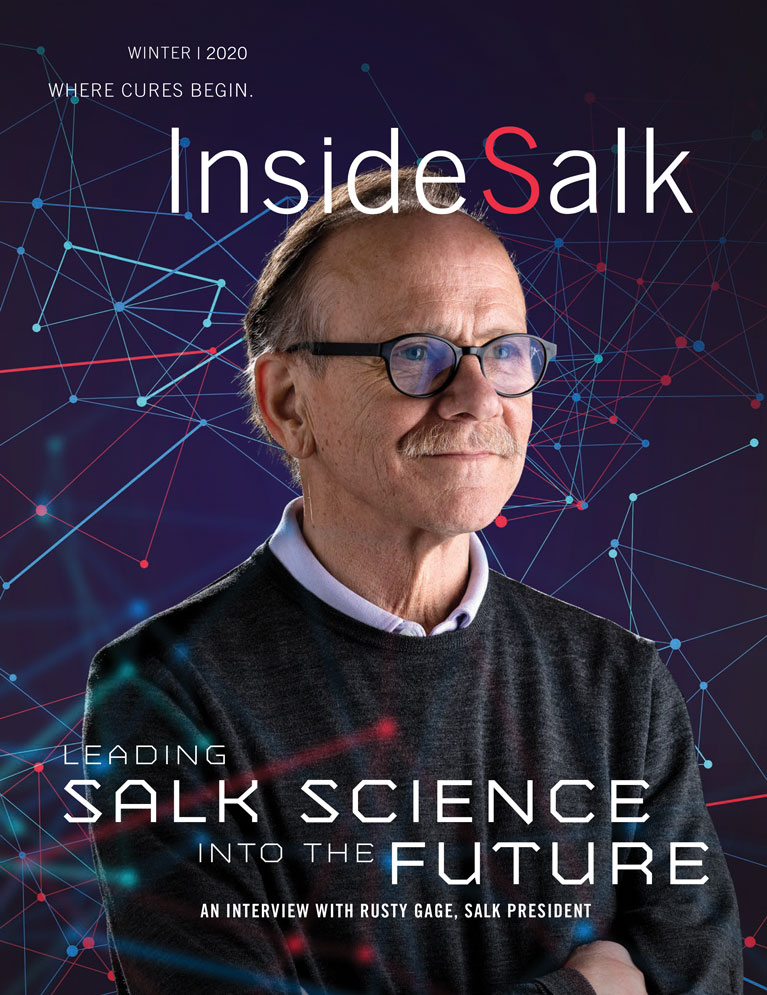

Lithium is considered the gold standard for treating bipolar disorder (BD), but nearly 70 percent of people with BD don’t respond to it. Now, Salk Professor and President Rusty Gage, co-first authors Renata Santos and Shani Stern, co-corresponding author Carol Marchetto, and colleagues have found that decreased activation of a gene called LEF1 disrupts ordinary neuronal function and promotes hyperexcitability in brain cells—a hallmark of BD. The work could result in a new drug target for BD as well as a biomarker for lithium nonresponsiveness

Read News ReleaseDiscoveries

Salk team reveals never-before-seen antibody binding, informing both liver cancer and antibody design

Some molecules are so elusive that scientists require a unique set of tools to capture their structure. That’s precisely how a multi-institutional research team led by Salk scientist Tony Hunter and Salk postdoctoral fellow Rajasree Kalagiri, featured in this issue’s “Next Gen,” defined how antibodies recognize a compound called phosphohistidine—an unstable molecule that’s implicated in certain cancers, such as liver and breast cancer and neuroblastoma. These insights could help researchers understand the molecule’s role in cancer pathways and also enable the design of more efficient antibodies in the future.

Specific bacteria in the gut prompt mother mice to neglect their pups

The microbiota are the microorganisms that colonize the body, but scientists are unsure about how they affect the brain. Professor Janelle Ayres, first author and former graduate student Yujung Michelle Lee and colleagues have identified a strain of E. coli bacteria that, when living in the guts of female mice, causes them to neglect their offspring. The findings show a direct link between a particular microbe and maternal behavior, demonstrating that microbes in the gut are important for brain health and can affect development and behavior.

Computational model reveals how the brain manages short-term memories

If you’ve ever forgotten something mere seconds after it was at the forefront of your mind, then you know how important working memory is. Although it’s critical in our day-to-day lives, exactly how the brain manages working memory has been a mystery. Now, Professor Terrence Sejnowski and Salk and UC San Diego MD/PhD student Robert Kim have developed a new computational model showing how the brain maintains information short-term using specific types of neurons. Their findings could help show why working memory is impaired in a broad range of neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, as well as in normal aging.

Read News ReleaseTeaching artificial intelligence to adapt

Getting computers to “think” like humans is the holy grail of artificial intelligence, but human brains turn out to be tough acts to follow. Now, Professors Terrence Sejnowski and Kay Tye, along with first author Ben Tsuda and colleagues, have used a computational model of brain activity to simulate “adaptability” more accurately than ever before. The new model mimics how the brain’s prefrontal cortex uses a phenomenon known as “gating” to control the flow of information between different areas of neurons. The findings could inform the design of new artificial intelligence programs.

Read News ReleaseNew protein helps carnivorous plants sense and trap their prey

The brush of an insect’s wing is enough to trigger a Venus flytrap to snap shut, but the biology of how these plants sense and respond to touch is still poorly understood, especially at the molecular level. A new study led by Salk Professor Joanne Chory and co-first author and Staff Scientist Carl Procko identifies what appears to be a key protein involved in touch sensitivity for flytraps and other carnivorous plants. The findings could help scientists better understand how plants of all kinds sense and respond to mechanical stimulation, and could also have a potential application in medical therapies that mechanically stimulate human cells such as neurons.

When it comes to feeling pain, touch or an itch, location matters

When you touch a hot stove, your hand reflexively pulls away; if you miss a rung on a ladder, you instinctively catch yourself. Both motions take a fraction of a second and require no forethought. Professor Martyn Goulding, first author Graziana Gatto and colleagues have mapped the physical organization of cells in the spinal cord that help mediate these and similar critical “sensorimotor reflexes.” The new blueprint of this aspect of the sensorimotor system could lead to a better understanding of how it develops and can go awry in conditions such as chronic itch or pain.

Read News ReleaseResearch catches up to world’s fastest growing plant

Wolffia, also known as duckweed, is the fastest-growing plant known, but the genetics underlying this strange little plant’s success have long been unknown to scientists. Now, a multi-investigator effort led by Todd Michael, research professor and first author of the paper, along with coauthor and Professor Joseph Ecker, reports new findings about the plant’s genome that explain how it is able to grow so fast. The research will help scientists to understand how plants put down roots and defend themselves from pests, with implications for developing plants that are optimized to increase carbon storage to help address climate change.

Read News ReleaseNew method could democratize deep learning-enhanced microscopy

Deep learning is a potential tool for scientists to glean more detail from low-resolution images in microscopy, but it’s often difficult to gather enough initial data to train computers in the process. A new method developed by Salk Assistant Research Professor Uri Manor, director of Salk’s Waitt Advance Biophotonics Core Facility, and first author Linjing Fang, Salk image analysis specialist, could make the technology more accessible by taking high-resolution images and artificially degrading them. The method could make it significantly easier for scientists to get detailed images of cells that have previously been difficult to observe, as well as allow scientists to capture high-resolution images even if they don’t have access to powerful microscopes.

Fast, portable test can diagnose COVID-19 and track variants

Salk Professor Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte and collaborators have developed a new viral screening test that can not only diagnose COVID-19 in a matter of minutes with a portable, pocket-sized machine, but can also simultaneously test for other viruses—like influenza—that might be mistaken for the coronavirus. Called NIRVANA, this test can sequence the virus, providing valuable information on the spread of COVID-19 mutations and variants.

How brain cells repair their DNA reveals “hot spots” of aging and disease

Neurons lack the ability to replicate their DNA, so they’re constantly working to repair damage to their genome. A new study by Salk Professor and President Rusty Gage and colleagues reports that these repairs are not random, but instead focus on protecting certain genetic “hot spots” that appear to play a critical role in neural identity and function. The findings give novel insights into the genetic structures involved in aging and neurodegeneration, and could point to the development of potential new therapies for diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other age-related dementia disorders.

Featured Stories

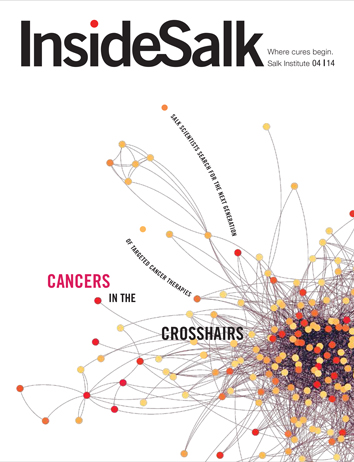

The aging puzzle comes togetherAging is a complex puzzle, but by applying a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach, Salk scientists are putting its many pieces together.

The aging puzzle comes togetherAging is a complex puzzle, but by applying a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach, Salk scientists are putting its many pieces together. Dmitry Lyumkis – A passion for problem solvingAssistant Professor Dmitry Lyumkis discusses what he loves about data and the scientific process, and which places inspire him outside the lab.

Dmitry Lyumkis – A passion for problem solvingAssistant Professor Dmitry Lyumkis discusses what he loves about data and the scientific process, and which places inspire him outside the lab.

Pamela Maher – Seeking treatments for Alzheimer’s diseaseFrom having a large garden to investigating compounds that plants make, Staff Scientist Pam Maher talks about how plants inspire her to find treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.

Pamela Maher – Seeking treatments for Alzheimer’s diseaseFrom having a large garden to investigating compounds that plants make, Staff Scientist Pam Maher talks about how plants inspire her to find treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Rajasree Kalagiri – Bound to phosphohistidineRajasree Kalagiri shares the serendipitous steps along her journey of scientific discovery from southern India to Southern California.

Rajasree Kalagiri – Bound to phosphohistidineRajasree Kalagiri shares the serendipitous steps along her journey of scientific discovery from southern India to Southern California.